Over the last year the loonie has declined significantly relative to the US dollar: the currencies were at par early last February, but the Canadian dollar closed under $0.92 US on January 10. That has been a benefit for Canadians who hold US equities: not only did the stocks deliver huge returns in their local currency in 2013, but we got a further boost thanks to the appreciation of the US dollar.

Unfortunately, the drop in our dollar has encouraged some ETF investors to attempt to exploit a buying opportunity. Trying to make currency plays is foolish at the best of times, but it’s especially unwise if you don’t fully understand how currency exposure works.

Meet Gerry, who uses the Vanguard S&P 500 (VOO) to get exposure to US stocks. This ETF is listed on the New York Stock Exchange and trades in US dollars. With the greenback riding high, Gerry plans to sell VOO and use the proceeds to buy an equivalent fund listed on the TSX: the Vanguard S&P 500 (VFV). Gerry tells his friends he’s selling US dollars high and buying Canadian dollars low while keeping his equity exposure the same. If the Canadian dollar eventually gets back to par, he’s going to switch ETFs again and make another tidy profit. Clever, isn’t he?

Not at all. Gerry’s strategy will just incur trading commissions, bid-ask spreads and currency conversion costs—and maybe realize a big capital gain—all while gaining absolutely nothing.

Understanding currency exposure

The problem is Gerry doesn’t understand that these two funds have exactly the same currency exposure. When you invest in foreign equities, your exposure comes from the underlying currency of the holdings, not the trading currency of the ETF. So whether he holds VOO or VFV, Gerry benefits when the Canadian dollar falls, and he suffers when it appreciates.

This idea might be easier to understand if we instead consider a single cross-listed stock, such as Royal Bank of Canada. A Canadian buying Royal Bank on the New York Stock Exchange in USD would not have any exposure to the US dollar, because the holding itself is denominated in CAD:

- Imagine the CAD and USD are at par when Gerry buys 1,000 shares of Royal Bank on the TSX for $70 CAD per share. His holding is worth $70,000 CAD.

- At the same time, his wife Sharon buys 1,000 shares of Royal Bank on the NYSE, where it is trading at $70 US. Sharon’s holding is valued at $70,000 USD.

- Now let’s say the loonie declines to $0.90 USD, but Royal Bank’s stock price remains at $70 CAD. In New York, the stock would now be trading at $63 USD.

- If Sharon sold her shares now, she would net $63,000 USD, which is a 10% loss in USD terms. But although Sharon has fewer US dollars than when she bought the stock, each is worth more CAD. And as a Canadian, she likely measures her investment returns in Canadian dollars. In CAD terms, her investment return is zero—just as it is for Gerry.

US stocks mean USD exposure

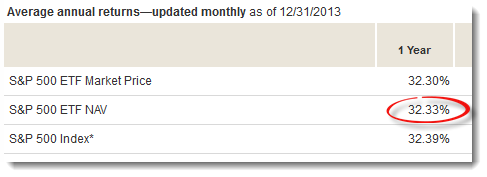

The same principle holds with VOO and VFV, which have identical underlying holdings denominated in USD. If Gerry owned VOO, he would have noticed it reported a 2013 return of 32.33% in US dollars:

But as a Canadian investor, Gerry would have benefited from the appreciation in the US dollar, which rose about 6.29% in 2013. When calculated in Canadian dollar terms, his holding in VOO was up 40.65%.

But as a Canadian investor, Gerry would have benefited from the appreciation in the US dollar, which rose about 6.29% in 2013. When calculated in Canadian dollar terms, his holding in VOO was up 40.65%.

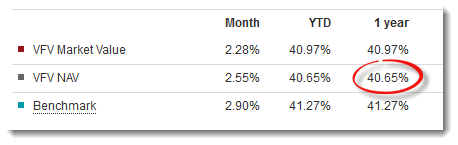

And if Sharon owned VFV, she would have visited Vanguard Canada’s website and found that her holding also returned 40.65% last year:

So if you measure your returns in Canadian dollars, it makes no difference whether you use VOO or VFV. Their holdings—and therefore their exposure to USD—are exactly the same, even though the ETFs trade in different currencies.

So if you measure your returns in Canadian dollars, it makes no difference whether you use VOO or VFV. Their holdings—and therefore their exposure to USD—are exactly the same, even though the ETFs trade in different currencies.

Hi Dan,

This question has been answered numerous times. But I am still trying to wrap my head around it. I sold my VTI shares in March and bought VUN. I have noticed both have gone up. I am wondering if the VUN index has increased less because the CDN dollar has depreciated.

Thanks,

Kevin

@Kevin: It’s confusing, for sure. Yes, if you are measuring your returns in Canadian dollar terms, then both VTI and VUN would go up in value if the Canadian dollar depreciates, even if the price of the underlying stocks remains unchanged. Your exposure to both US stocks and the US dollar is identical whether you use VTI or VUN.

Very well explained. Thanks for your very insightful posts.

So at the end of the day, is there any benefit to buying VTI over VUN except the lower MER? Does the choice of ETF matter depending on whether it is held in registered or unregistered accounts?

@Victor: https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2013/12/09/ask-the-spud-when-should-i-use-us-listed-etfs/

What about the following situation?

– Imagine the CAD and USD are at par when Gerry spends 1,000 CDN on Royal Bank (RB) on the TSX at $100 CAD per share. He has 10 shares of RY.

– At the same time, his wife Sharon spends 1000 USD on Citibank (CB) on the NYSE, where it is trading at $100 US per share. Sharon has 10 shares of CB.

– Now let’s say the loonie declines to $0.90 USD the next day and the stocks don’t move in price.

– Sharon sells her 10 shares of CB and nets 1000 USD. She then exchanges that to CDN (netting ~1100) and uses that money to buy RY. She is able to buy 11 shares.

– Sharon owns 11 shares of RY whereas Gerry owns only 10.

– The corollary of this also works (i.e. CDN appreciates, you gain more CB stocks, than if you had bought them outright when CDN was low).

Basically, this is no different to buying US dollars when CDN is high, and selling them when CDN is low. Historically, the CDN will fluctuate anywhere between 0.7 and parity with USD. So when things are par, buy US, and when CDN is low, buy CDN. Swap out RB and CB for TSX-ETF and DJI-ETF, and you’ve just turbo-charged your exchange-linked investments. Wouldn’t this work?

@Santos: Your description is accurate, but all you are doing is speculating on currencies, and you’re overlaying equity risk on top of it. Not only are you moving between USD and CAD, expecting to buy low and sell high, but you are also moving between completely different securities, a Canadian equity index fund and a US equity index fund. That means you could be exactly right on the currency and still lose because the equities don’t behave the way you expected. So, no, it wouldn’t work.

Thanks for these great articles !

It was counter-intuitive at first for me to see the share of the model portfolios that are dedicated to Canadian assets (~50%), compared to the size of the Canadian economy. Is this the recommended way to limit currency exposure?

@Thomas: Thanks for the comment. I’m assuming you’re lumping bonds in with the “Canadian assets.” In general it’s not necessary to have international diversification in fixed income:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2014/08/29/ask-the-spud-should-i-use-global-bonds/

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2012/05/22/ask-the-spud-does-home-bias-ever-make-sense/

Thanks for writing this excellent article.

Let’s say Gerry owns CAD 100,000 of XGRO in tax sheltered accounts and decides to measure his success going forward in USD due certain changes in his life. Current exchange rate of 1.41 CAD for 1 USD is very unattractive for him. He believes CAD will revert to historic time average of 1.25 CAD in few years.

Assuming CAD will revert to historic average in few years, what strategies will you suggest Gerry.

@Andy: There may be reasons to consider hedging currency based on where you plan to retire and/or what other types of investments you hold (for example, US real estate). However, forecasts about the CAD-USD exchange rate have no value, any more than forecasts about the stock market. If you believe the USD will fall relative to the loonie, then you should use currency hedging. But you would just be guessing.