Trading commissions get a lot of attention from ETF investors, and rightly so. But depending which ETFs you use and the size of your trades, the impact of bid-ask spreads may be larger than you thought.

The bid price is what you expect to receive when you sell shares, while the ask price (or offer price) is what you would expect to pay to buy them. The difference between the two is called the bid-ask spread, and it represents the profit taken by the market makers.

Unlike with individual stocks, trading volume doesn’t have a major effect on the bid-ask spread of an ETF. The liquidity of an ETF is largely determined by the liquidity of its underlying holdings: if the fund holds frequently traded large-cap stocks, its bid-ask spread should be very tight even if the ETF itself doesn’t trade very often. If the ETF holds micro-cap stocks or illiquid bonds the spread will be wider even if units trade frequently.

The underlying story

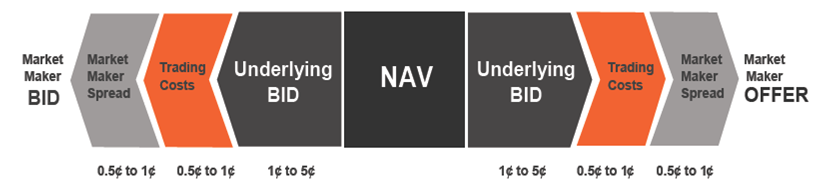

But that’s not the whole story. If the liquidity of the underlying holdings was the only factor, ETFs in the same asset class would have more or less identical bid-ask spreads, and that isn’t the case. The bid-ask spread of an ETF also includes the costs involved in creating the ETF units. Think of it this way: you could buy all the stocks in the S&P/TSX 60 directly, or a market maker could buy them for you, package them up, and sell them to you in the form of an ETF. In both cases you’ll pay the bid-ask spread on the underlying securities, but in the second scenario you also pay the costs involved in bundling the securities and selling them as ETF units. This diagram, supplied by Horizons ETFs, illustrates this idea nicely:

In the centre is the net asset value of the fund. The distance between the NAV and the fund’s bid and ask prices gets wider as one adds the spreads on the underlying stocks or bonds, plus the additional costs to assemble and trade the ETF units. The good news is, even when you total up these costs we’re still only talking about a spread of $0.01 to $0.04 cents in most cases, though there are certainly exceptions.

What’s that spread costing you?

How much does this spread cost you when you buy or sell ETFs? It’s best to think of your cost as half the spread, because both the buyer and seller give up a little in each trade. Although you can’t know an ETF’s precise net asset value during the trading day, you can expect it to be the midpoint between the bid and ask prices. If you get a quote with a bid of $19.98 and an ask of $20.02, the fund’s NAV is likely right around $20. That means your transaction cost when buying or selling is about $0.02 per unit, or half of the four-cent spread.

I decided to get some quotes for a number of Canadian ETFs to see the range of bid-ask spreads. (All of these were obtained on the morning of November 20, though it should be noted that spreads are not consistent, even from hour to hour.) I’ve also included the number of shares you could buy with $10,000 and the resulting transaction cost based on half the bid-ask spread:

| Exchange-traded fund | # Shares | Bid | Ask | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iShares S&P/TSX 60 (XIU) | 513 | 19.46 | 19.47 | 2.56 |

| Horizons S&P/TSX 60 (HXT) | 418 | 23.9 | 23.91 | 2.09 |

| iShares S&P 500 (XUS) | 426 | 23.41 | 23.42 | 2.13 |

| Vanguard S&P 500 (VUS) | 300 | 33.26 | 33.28 | 3.00 |

| BMO S&P 500 (ZSP) | 483 | 20.65 | 20.68 | 7.25 |

| iShares MSCI Emerging Markets (XEM) | 399 | 25.02 | 25.04 | 3.99 |

| BMO MSCI Emerging Markets (ZEM) | 637 | 15.62 | 15.68 | 19.11 |

| Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets (VEE) | 382 | 26.12 | 26.15 | 5.73 |

| BMO Aggregate Bond (ZAG) | 653 | 15.28 | 15.3 | 6.53 |

| iShares DEX Universe Bond (XBB) | 330 | 30.23 | 30.24 | 1.65 |

| Vanguard Canadian Aggregate Bond (VAB) | 408 | 24.41 | 24.44 | 6.14 |

| iShares Global Real Estate (CGR) | 475 | 20.95 | 21.01 | 14.25 |

| iShares S&P/TSX Small Cap (XCS) | 672 | 14.81 | 14.86 | 16.80 |

| iShares S&P/TSX Venture (XVX) | 839 | 11.81 | 11.91 | 41.95 |

Bid-ask spreads are an inevitable cost of ETF investing, and if you’re buying and selling small amounts they’re not significant. But if you’re placing large orders for ETFs with wide spreads they can be a bigger factor than a $10 trading commission. Be alert when you place your trades and always use limit orders to avoid surprises.

Nice to be aware of for sure. So what I take away from this is that for most large/”simple” ETFs representing large/liquid/common holdings, like XIU, or VUS, or many of the others on your list, the cost is basically negligible and a non-issue as a percentage. Even the “fringe” ones like XVX, you’re still talking about a 1-time fee of 0.4%, which is unlikely to make any material difference in your retirement, assuming you’re not buying/selling 4x/year (which would be another issue entirely anyway).

I am curious about the difference between ZEM and XEM. They track the same index, so one should expect the portion of the spread representing the underlying bid/ask to be equal? Therefore the difference must be in the market maker or trading costs portion? So is BMO extracting higher fees here than iShares?

Could it even just be “rounding error” given the fact that the BMO fund trades at a lower price? You’re talking about a 6 cent spread – so even a rounding up by one cent rather than down makes the cost in your table 20% higher.

This is something that I’ve commented on before regarding Vanguard Canada’s historically high bid-ask spread. When I last looked, I saw up to a 10 cent spread and I avoided them because of it but now look like it has closed a bit.

ETFs that have a high return of capital that erode their NAV, will have a higher cost to sell later so one should also factor that in if you are buying a significant amount that you intend to hold for a long time.

The best you’ll get is a 1 cent spread with ETFs that have a high NAV that goes up over time.

It might be worth showing how Canadian ETFs compare to US ETFs.

VTI 107 92.89 92.9 $0.54

VWO 240 41.51 41.52 $1.20

VEA 244 40.88 40.89 $1.22

VXUS 192 51.82 51.87 $4.80

@Willy and Brian: You both raise some good points.

RE: “I am curious about the difference between ZEM and XEM… So is BMO extracting higher fees here than iShares?” Remember that BMO and iShares are not the market makers: they employ third parties to do this. ETF providers have a vested interest in keeping the spreads as low as possible in order encourage investors to use their products.

As both of you alluded to, ETFs with higher unit prices are much less affected by bid-ask spreads. The common practice in Canada seems to be to issue ETFs with unit prices around $20. You rarely see them exceeding $30. But in the US, it is common to see much higher prices, which actually makes trading less expensive.

The cheapest one I could find is SPY, which trades at one-tenth of the S&P 500’s index value. That’s currently about $179 per share with a spread of one cent, which means buying $10,000 worth would cost one shiny quarter.

@Willy only you can look at your situation regarding the amount invested and the number of trades (buys or sells) per year to determine if they are significant for you. Without getting into my investment strategy lets just say I’m a bad boy and I trade more often than a usual Couch Potato investor, so it matters to me.

Regarding ZEM and XEM. Yes, it’s the market maker. However, there is a trade off here in that ZEM has a lower MER and thus if you look over the last year the total returns are 10.15% and 9.17% respectively. One always needs to look at the complete picture.

By the way, I calculated this by charting and comparing total return using tmxmoney charting with adjust for splits and dividends turned on. I’m not associated with them but I find it’s a good free tool for these sorts of comparisons.

@CCP Nice one on SPY. The volume on SPY is ***HUGE***. Because of that buyers and sellers are often trading directly, removing the market maker who’s primary roll is to create liquidity when there is none which isn’t the case with SPY.

Isn’t it possible to avoid some or all of the spread by placing limit orders closer to NAV (by bidding slightly more or offering at slightly less than the market maker)? This requires some patience and baby-sitting, but it’s worthwhile if you’re making a large trade. To me, large bid ask spreads are not necessarily a problem if the fund has reasonable volume such that offers near NAV get picked up pretty quickly.

Obviously, there’s not much room to get closer to NAV when the spread is a penny.

@AndrewF the NAV at any point during the day is somewhere near the middle of the bid-ask prices. If you place your order there for an ETF that has a large spread it is unlikely to ever get filled. If it does get filled after a long wait, likely what is happening is the whole market just moved along with the bid-ask prices. In that case, you’d still be better of to have just bought a low bid-ask ETF immediately and moved with the market (assuming market exposure is the reason why you are purchasing in the first place.)

@AndrewF: As Brian points out, getting clever with limit orders is likely to just see your order left unfilled. A lot of people seem to think they can get a better price by placing limit orders, but this isn’t true. It’s not haggling at the bazaar. In theory, a market order and a limit order should get filled at the same price. But the limit order allows you to avoid surprises if the quote was stale.

So you’re saying that a bid at 19.99 would go unfilled while transactions were happening at the market-maker’s bid of 19.98 (assuming an ask of 20.00, say)? Can you explain why that would be the case?

For some less liquid securities with wider spreads, I have had some luck placing limit orders at the bid-ask mid point.

@AndrewF here’s a hypothetical. Let’s say there are two ETFs, XXX, YYY that track the same index and have the same MER. XXX has a spread of 10 cents and YYY of 2 cent. Let’s say at 10:00am the NAV is $20.00 and XXX is trading at 19.95 bid and 20.05 ask and YYY is trading at 19.99 and 20.01. You could put in a limit order for XXX at $20.00. It won’t get filled immediately. Now let’s suppose the market moves down 5 cents and by 12:00am the NAV is 19.95, XXX is 19.90 and 20.00 and YYY is 19.94 and 19.96. Your order gets filled now, but had you bought YYY AT THE SAME TIME AS THE ORDER GETS FILLED, it would on cost only 19.96… 4 cents cheaper. If the market had gone up by 5 cents, your order wouldn’t get filled for XXX. However, had you bought YYY at 20.01, it would be at 20.04 and 20.06 and you would have just made 3 cents.

Hard to explain but if you always compare prices AT THE SAME TIME of the trade, the lower bid-ask will always be the better choice.

If you are not comparing the same times, then you are mixing in market movements.

@Andrew F

An example would be when I’m buying one of my ETFs (CBO), which generally has fairly stable prices, and I see that the ‘last’ price was 19.76 (therefore my bid = 19.76, ask = 19.77), and I still have an open order for the same price. It’s only when the seller’s ‘ask’ dips down to 19.76 that you order will be filled.

However, you may get the impression that you are able to stick it to the market markers because the ask dips for a brief moment, likely due to a change in value of the underlying securities.

BTW – first time commenter, reader for a while. Great job on the site CCP!

Thanks for the comment, Kevin.

It might be helpful to think of the bid-ask spread as the retail markup. If the bid is $19.98 and the ask is $20.02, you might think you can place a limit order at $20 and have it filled because that is the presumed NAV. But that’s like asking a car dealer to sell you a vehicle at his invoice price with no markup.

I’m not assuming the market maker will change their spread. I’m assuming that another market participant may want to take the other side of the trade. Why would a bid at 19.99 go unfilled with a bid-ask of 19.98/20.02 from the market maker. If another market participant submits a market order to sell the stock, would they get my bid of 19.99 or the market-maker’s bid of 19.98?

I acknowledge that sometimes when you place a limit order between the bid/ask, sometimes the price merely moves such that the your price moves beyond the mm’s bid/ask and they fill your order.

Put another way… isn’t the only way to always pay the full spread for everyone to only trade with the market maker?

Technically, you are correct but in practice you are mostly wrong. ;-) If an ETF has a large number of non-market maker transactions then it will be by definition a low bid-ask spread ETF. E.g. SPY. If it’s a typical low volume Canadian ETF that has a high bid-ask spread then by definition your strategy won’t work very often because 90% of the time you’ll be trading with the market maker… but if it does start working it will become a low bid-ask spread ETF. It’s circular.

By the way, I’ve tried this a few years back when I didn’t get it. I can confirm it didn’t work for me except occasionally with small orders.

I always like to keep things in perspective with respect to the big picture. The message that is being driven home here is that the use of limit orders is a good thing to avoid surprises when purchasing large blocks of shares. Also, a broad based etf with a low spread will usually be filled more quickly/easily than a less active etf.

So as long as the “cost” of the spread is below the cost of the trade and also below my Tim Horton’s/Starbucks coffee limit for the day, then I am probably OK. If my broker charges me $9.00 for the trade and spread cost is $3.00 than I am probably not going to shed a tear.

This is because my aggregate ETF portfolio MER is 0.37 where the average mutual fund MER is 2.5. I am still miles ahead of the game when compared with “traditional” investments.

If I rebalance twice a year (Jan/Jun), then my costs will be much lower than if I used a traditional fund (Low cost index funds excluded) regardless of the additional cost of the spread.

Perhaps I have too simplistic a view, but I just can’t get excited over a few pennies here and there. I am much more concerned with asset allocation and the selection of the right etf at the right cost.

Your mileage may vary. rob…

@Robert_M For the vast majority of Couch Potato investors with smaller portfolios you absolutely are correct. Thanks for reinforcing the point and putting it in context.

But it’s not meaningless in all situations. For example. suppose someone is closer to retirement with say a $1m portfolio that they want to convert to a Couch Potato portfolio. Using ETFs with a $0.10 spread could be costing them $2500 vs $250 with a $0.01 spread. $2250 savings is more than a few pennies.

If you have large portfolio or you’re using a more active strategy, then the costs can become very significant.

Like everything, it’s best to be well informed and then determine whether it matters for your situation.

Great stuff Dan! This is a very important but hidden cost of investing in ETFs – and more important as the market shifts away from the most broadly-diversified, cheapest and most liquid ETFs to more narrowly focused funds. Love the graphic!

@Robert_M: It can also come into play when choosing between ETFs. The market is closed right now so I can’t give exact numbers, but for example, the Powershares and Schwab International Fundamental Indexes (PXF vs FNDF and PDN vs FNDC) are very, very similar, but the Schwab ETFs have much tighter bid/ask spreads. (If I recall correctly, it’s something like 20 cents for PDN vs 2-3 for FNDC.) Neither one is necessarily a bad investment, but the spread certainly factors in when comparing the two.

Of course, if you stick to the large, broad-market funds, they all tend to have pretty tight spreads, so as you say, it’s a non-issue.

For fun, I made up a spreadsheet to compare the total costs of buying $10,000 of Couch Potato recommended Canadian Equity ETFs at a brokerage that charges $10 per trade and then selling them a year later.

Total Cost = MER + Bid/Ask Spread + 2 x Trade Commission.

HXT 0.07%+0.17%+0.20%=0.44%

VCN 0.12%+0.22%+0.20%=0.54%

ZCN 0.17%+0.16%+0.20%=0.53%

XIU 0.18%+0.20%+0.20%=0.58%

Just for fun, let’s compare this situation to TD e-Series Canadian Index

TDB900 0.33%+0%+0%=0.33%

Surprise! :)

Even with $0 trades, e-Series would still be better for the small investor. Things would only get worse for a small investor making regular contributions to an ETF portfolio.

Summary, ETF investors focus in on MER’s but MER’s are not the only thing to watch.

@Brian: Hopefully most CP investors are holding funds for longer than a year though, right? As soon as you hold for two years, they’re about the same as the e-fund, and beyond that, the ETFs all win out.

That said, for those willing to make the effort, I think a great approach is to build up funds with regular contributions in e-funds, then to switch them over to ETFs in lump sums every year or three.

@Nathan, you answered your own question. Yes, they should hold for more than a year but if you do 2 or more purchases per year it’s the same problem.

Every person’s situation is different but the only point I was trying to make was that MER is not the only thing to look at when evaluating costs and my example was just meant to show that.

If I wanted to make a crazy example, I would have brought up the bid ask spread on ZRR. :)

I had wanted to read up on why bid-ask spread was a cost to the buyer or seller. This blog made it clear — car salesman’s analogy helped :) . It’s like paying commission to two entities -the broker and the ETF maker.

I’ve always used market orders, but you make a good point about using limit orders. There is one thing that I’m not clear on. If you submit a limit order, do you get the price you specify or the *best* price? For example, if the ask for a stock is $20.00 and you submit a limit order at $20.05, could you get the stock at a lower price (for example at $20.02 that being the market price at the time of your submission) or would you only get the stock when it was $20.05 or higher?

@Smithson: Great question, and a very important, frequently misunderstood point. When you place a limit order, you get the best price available, assuming that price is within the limit specified. If the current ask price is $20 and the quote is current, you will pay $20 even if you submit a limit order at $20.05.

Many people seem to think that by entering a limit order they are “tipping their hand” that they’re willing to pay more or accept less. That’s not how a stock exchange works. Buy and sell orders are matched at the best price available.

@Brian. If the twice yearly trade is just for rebalance, your comparison isn’t quite “apples to apples”. The bid/ask spread cost is not on the entire $10,000, it’s on a (likely) much smaller amount. There’s a chance the ETF could come out ahead, but no way of knowing without knowing the actual dollar amounts on the trades.

Of course for other reasons the mutual funds are likely the better choice at $10,000.

Another good post Dan.

I don’t mean to sound nit picking, but the statement “The difference between the two is called the bid-ask spread, and it represents the profit taken by the market makers.” is not quite correct.

Per http://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/profit.asp Profit is Revenue minus Expenses.

I would suggest that the bid-ask spread represents “Revenue” not “Profit that flow to the market maker

Thanks

@CPP: Thanks for clarifying how a limit order works. So if I really want a buy order executed on a given day, is there a downside to deliberately placing a limit order say 10 cents over the ask so that my order is filled quickly?

@Smithson: In most cases that would end up being fine, but it seems a little careless to me: it’s not much different from placing a market order. The point of the limit order is to ensure that the quoted price is close to the actual market price and to help you estimate your cost. I’d suggest using a limit order about two cents above the ask (or below the bid if selling), or up to four or five cents if the spread is wide already.

@CCP: Thanks! I will use limit orders in the future.

Since most of my purchases these days are for rebalancing, I mostly base my limit price on my rebalance amount. I’ve created a “purchase calculator” in Excel where I input how much I wish to purchase and the fund’s current unit price. My Excel formula then tells me how many units I can buy for that amount (taking into account commission), and what limit price I need to put in to not exceed funds available for purchase.

Example: Say as part of rebalance, I need to purchase $2571 shares of ETF XYZ. Current price is $24.94. Trade commission is $9.95. My formula says to purchase 102 shares with a limit order of $25.10.

I have noticed this issue but I have also found that, at TD discount broker at least, sometimes I get part of the order filled at a “better” price than I put in my limit order, just for say half of the order but very occasionally the whole order. I never use market orders.

I find most of my orders are filled in blocks, sometimes with considerable time separating each block. I don’t make trades very often, just rebalancing.

BTW is anyone finding the need to rebalance these days using, say, Swedroe’s 5/25 rule?

I am new to investing. I just spent the last 10 minutes reading this article and the comments. I have learned more in the last 10 minutes than in the last 6 days. Thank you all for being avid contributors. New investors like myself need people like you folks, debating points, to help fill the gaps in our knowledge.

hi Dan,

Last night, I went through the Vanguard web site and noticed the huge difference between VEE returns and what the index it follows did during the same periods. Since I own VEE, I am a little worry the MER isn’t really telling me the whole story about costs. I know about tracking error but the difference is really important (see the 3 year annualized returns). I also looked at XEC and there seems also to be something “wrong”. Should I be worry? Thanks!

@andre: I don’t think you need to worry, though it is worth trying to figure out the reasons for these tracking errors. In the case of VEE, this fund changed its benchmark index in 2013 (from MSCI to FTSE), so that helps explain why the one-year numbers look fine but the 3-year numbers look off. The MSCI and FTSE indexes are quite different. In the case of XEC it’s harder to say. This is a new fund that may have incurred some start-up costs in its first year.

Foreign withholding taxes are also a factor: they will always increase the tracking error of international equity funds. Sometimes short-lived pricing anomalies come into play as well. These tend to disappear over time:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2010/04/23/international-tracking-error-part-1/

I hedge half of my foreign equities, and the current bid ask spread on VEF is 35.52/35.83. If I am planning to purchase a significant amount, is trading at such a significant spread advisable? Not sure if the spread should be expected to decline any time soon… Thank you.

Further to my last post, is XFH a reasonable alternative to VEF? The bid ask is a little better at 19.75/19.86. Again, curious as to whether a limit order at the ask price is a good option at this time. Thanks again.

@CS: That spread on VEF seems abnormally wide. Four or five cents is much more normal. Based on the time you posted your comment I wonder whether you were getting a quote when the markets were closed?

I came back to review this post to better understand what happened to me today. I thought I understood things but now I realise I had missed some finer points. I have a large non-registered portfolio that I had planned never to touch to minimise unnecessary tax, unless rebalancing became really necessary. But I needed to liquidate a large portion to generate cash for my daughter’s purchase of a house. In liquidating a large block of HBB I found that it trades relatively thinly, and the spread is large, about 10 cents today. I bobbled the initial try by placing my limit exactly at the existing bid price; but only 103 shares sold, which was the size of the existing bid. When nothing happened after a long wait, I phoned the order desk, and I was able to find out that there was a large secondary bid 5 cents lower. I changed my limit to 7 cents lower and the remainder immediately filled at only 5 cents lower. This kind of information is not likely to be accessible by the average investor, even with the help of the QuoteMedia tool that CCP introduced us to in the September 12, 2015 post, so I guess, depending on the size of the spread, the size of the bid (or ask), and the number of shares requiring trade vs the underlying trading volume, it may be worth considering a higher cost telephone order to lower the cost attributable to the bid-ask spread.

The reason I say this is that in theory your order to sell (which I presume becomes an “ask” at the order desk) should be matched to the highest bid. But in the chaos of things, or maybe in the convenience of matching your “ask” to an existing bid of about the right size without searching too much in the secondary markets, your order may get assigned to a lower bid. It is useful to get some specific information as to what secondary bids actually exist. Otherwise you are forced to make an arbitrary guess, and if you guess a figure too low below the existing bids, this may attract a lower new bid price than would be actually required to secure a timely sale before the market moves, which may be downwards.

I also sold some other ETFs, mostly uneventfully (ZEA had a spread of only 2 cents), but ran into a slight snag selling ZEM. Again there was a modest bid-ask spread on my regular trading web platform, in this case 4 cents (16.67 to 16.71), but I noticed there had been no trading for more than an hour since the markets opened at 16.71, with a scattering of opening trades at various prices from 16.71 to 16.65 (this information from QuoteMedia), and the existing bid at 16.67 was only for 100 shares. I was on the phone with the order desk and he told me I would be able to get my intended block of 1100 shares filled if I lowered my limit to 16.62, so I put in a sell order with a limit of 16.60. It quickly sold at an average price of 16.6282. But checking several hours after the fact, on my usual trading website, the history for the day for ZEM claimed that the price on the TSX was UNCHANGED at 16.66 from the day before, with no details of any trades showing, but acknowledging that the volume that day was 2553 shares on the TSX; but the high was 16.71 and the low allegedly was 16.66.

I checked back on QuoteMedia, and trawling through the secondary markets for ZEM, some of them also trading on the TSX, found that some indeed had sold for below 16.66, so must have included my ZEM shares, but had not been recorded as such on the data available through my own web-based trading platform.

I’m sorry for the detail, but I wanted to include the information to demonstrate what I as an average CP investor was able to find out at the time of trading, and how much I couldn’t. It appears there is only so much you can do to minimise the losses due to large bid-ask spreads at the time of trading. This loss can be unpredictably high for some ETFs. In particular HBB seems to have large spreads, despite the liquidity of its underlying bond assets, and I suspect that this is due to its slightly complex structure and its relatively thin trading. A pity, because it is otherwise ideal to form the backbone of a safe non-registered portfolio. Bottom line, do all you can to minimise costs at trades, but still beware of the unavoidable hidden costs of bid-ask spreads, the underlying topic of this post. Best, do all you can to minimise trading in the long term strategy for this reason if your portfolio includes large blocks of ETFs with larger than narrow spreads. This can cause a higher than expected cost of generating cash; I’m not sure if or how this cost could be reduced with more lead time and research; but this option was not available to me at this time.

I tried to maximise liquidity by trading early to middle of the day. But I wonder in retrospect if the choice of Friday as trading day in Toronto had any effect on liquidity and spreads for ZEM.

This cost also occurs at the front end, of course. It’s been such a long time since I originally bought the ETFs making up the portfolio, I forget the details. But even if I had been aware then of the hidden high costs of buying ETFs with large spreads there’s not much I could have done, even with hindsight, except to try to plan meticulously, and not have to fine tune too much, or worse, redo things with re-trading of large blocks.