Q: I noticed that over the long term (10 to 20 years) the average returns of your model portfolios are quite similar regardless of the asset allocation, but the maximum losses vary dramatically. Would you say that people saving for retirement may as well be less aggressive, since their goal can still be reached with less risk? – L.V.

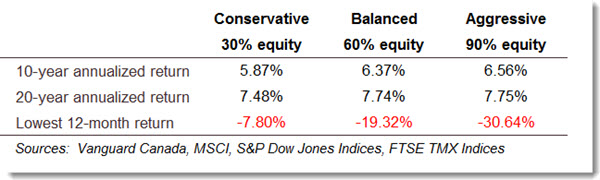

One of the first principles of investing is that more risk should lead to higher returns, while playing it safe comes at the cost of slower growth. That’s why I was surprised when we compiled the historical returns of my model ETF portfolios. Over the 10- and 20-year periods ending in 2014, you were barely rewarded for taking more risk:

As you can see, a portfolio of 30% equities and 70% bonds enjoyed an annualized return of 7.48% over 20 years, while portfolios with 60% and 90% equities returned only slightly more. Yet equity-heavy portfolios would have endured a much rockier ride: the investor with 30% stocks never suffered a loss of even 8%, while the poor sap with 90% equities lost almost a third of his portfolio during the worst 12 months (which was February 2008 through March 2009).

When you look at those numbers, it’s hard to see why anyone would take risk in the stock market when the price is so high and the payoff so low. If you’re a long-term investor, why not pick the most conservative portfolio and reap the rewards without the sleepless nights?

Bully for bonds

Before answering that question, it’s important to understand why the model portfolios performed so similarly over the last 20 years, and then to consider whether the next 20 years are likely to unfold the same way.

Let’s take a step back and consider the bigger picture. According to the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2015, the world stock market has delivered an inflation-adjusted average annual return of 5.2% since 1900, compared with 1.9% for bonds. It seems reasonable to conclude that patient investors will usually be rewarded for the risk they take when investing in equities. But that doesn’t mean those rewards will show up over every period or in every country, and the last 20 years in Canada were decidedly unusual.

The model portfolio performance numbers begin in 1995. In January of that year, 10-year Government of Canada bonds were yielding 9.34%, well above their historical average. During the next 20 years, yields trended consistently downward, and by the end of 2014 that 10-year Government of Canada bond was paying 1.79%.

When yields fall, bond prices rise, so these plummeting yields led to a huge bull market in bonds. During the 20 years ending in 2014, the broad Canadian bond market delivered returns of about 7.2% annually. After inflation, those returns were still well over 5%, compared with our 1.9% long-term global average. What’s more, only two calendar years saw negative returns (1999 and 2013), and the biggest loss was a measly –1.2%.

During the same two decades, Canadian and US stocks (in Canadian dollar terms) both delivered about 8.8% before inflation, but international and emerging markets stocks came in at just 4.6%. And in order to get those mediocre returns you would have had to endure the dot-com bust (three consecutive years of negative returns from 2000–02) and the worst market crash (2008–09) since the Great Depression.

All told, then, the 20 years ending in 2014 were a magnificent time to be a bond investor in Canada, and a pretty difficult one for anyone with a global equity portfolio. If you have a time machine, it certainly would make sense to transport yourself back to 1995 and put your entire portfolio in 20-year bonds.

The past is not prologue

But does it make sense to expect similar results going forward? It’s hard to imagine how anyone could make that argument. While no one can forecast equity markets with any accuracy, bonds have a narrower range of possible outcomes. Interest rates have fallen even further in 2015, and if you buy a 10-year Government of Canada bond today and hold it to maturity your annual return will be just over 1.3%. And although rising rates would lead to higher expected returns in the future, it’s difficult to see how the broad bond market could possibly deliver returns like those of the previous 20 years.

So while it is tempting to expect annual returns of 7% from a portfolio of 30% equities and 70% bonds, it’s probably fantasy. That doesn’t mean you should take more risk in your portfolio than you can comfortably handle. It just means your financial plan should use much more conservative assumptions. And it probably means you should plan on saving more.

@Charles: Dollar-cost averaging has no effect on the model portfolio returns:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2015/07/20/how-contributions-affect-your-rate-of-return/