One of the most common excuses made by forecasters is, “I wasn’t wrong, I was just off with the timing.” But that fails to acknowledge that timing is an integral part of any forecast. Imagine a weather reporter predicting rain on Monday and claiming he was still right when the downpour doesn’t arrive until Thursday.

We need to demand the same accountability from the commentators who have been predicting rising interest rates for about five years now. Even if rates do rise significantly in the next year or two—which would cause bond prices to fall—they won’t be able to claim their predictions were accurate but merely late. The only honest thing to do is admit they were dead wrong—and to stop making forecasts that encourage investors to abandon their long-term plans.

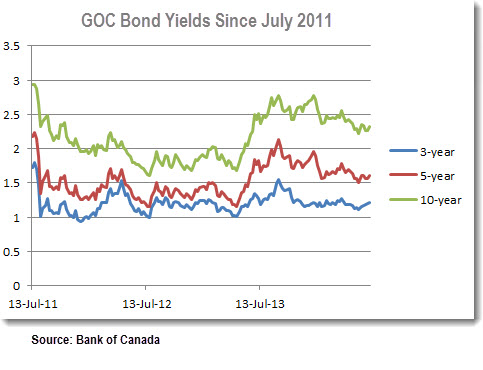

The bond bears had already been growling for a couple years when I wrote a column on this topic for a 2011 issue of MoneySense. The article quoted an advisor who had arrogantly told me “the bond index funds you recommend in your Couch Potato portfolios will soon be a disaster.” Like just about every other commentator at the time, he simply assumed rising rates were inevitable. Yet here’s how the yield on Government of Canada bonds changed in the three years since his gloomy prediction:

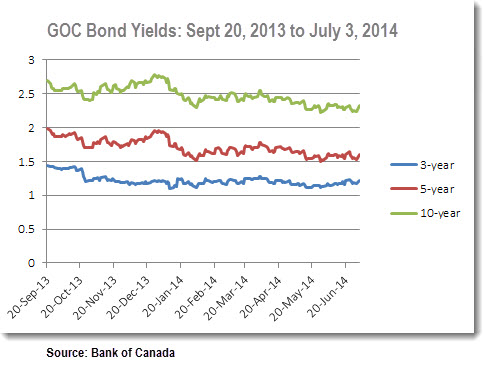

The soothsayers had a brief opportunity to be smug in 2013, when rates spiked in the spring and caused bond prices to fall sharply. In September of last year, another advisor proclaimed that “in a very low rate environment, where rates have nowhere to go but up, you’re pretty much guaranteed to in a best-case scenario break even or, in a more likely scenario, lose some money.” As it turned out, rates began to fall almost as soon as those words were out of his mouth. This chart shows the trajectory of Government of Canada bond yields in the nine-plus months since that article appeared:

What if you just stayed the course?

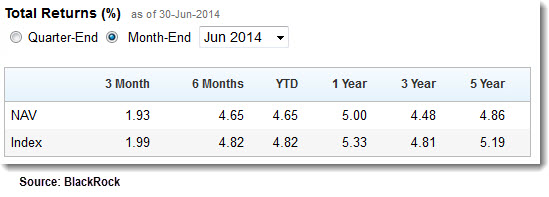

And how would you have fared if you’d simply held a broad-based fund like the iShares Canadian Universe Bond (XBB)? You would have had some volatile months, but over the most recent one-year, three-year and five-year periods, bonds have defied all expectations with returns in the neighbourhood of 4.5% to 5%:

I need to stress that I’m not arguing anyone should have expected bond returns would be this good. Nor should we ignore the very real possibility of a bear market in bonds, perhaps with a couple of years of negative returns. The point is simply that investing is about understanding and managing risks, not trying to avoid them with tactical moves that frequently backfire.

I need to stress that I’m not arguing anyone should have expected bond returns would be this good. Nor should we ignore the very real possibility of a bear market in bonds, perhaps with a couple of years of negative returns. The point is simply that investing is about understanding and managing risks, not trying to avoid them with tactical moves that frequently backfire.

Instead of predicting “disaster” or declaring “rates have nowhere to go but up,” advisors should help investors understand what could happen to bonds if rates rise or fall, and then encourage them to choose a fund appropriate to their time horizon and risk tolerance.

If you’re uncomfortable with volatility, for example, use a short-term bond fund or a ladder of GICs for your fixed income holdings. If your time horizon is several decades into the future, you can use a broad-based fund with a longer duration: your risk of loss is higher, but so is your expected return. The important idea is that your investing decisions should be based on your personal goals and a clear understanding of risk—not on the useless forecasts of people who claim to know the unknowable.

In your first paragraph, I think you go too easy on failed forecasters. Timing is *everything*. A directionally correct forecast with wrong timing is worse than useless, and far more harmful, especially in this arena, than no forecast at all.

It’s certainly a taken a lot longer than I expected. As a long-term investor I would be able to wait out any drop in bonds. However their expected returns are low at best and since I know I don’t need that protection I’ve avoided them. All investors would be wise to base their decisions on what they can handle rather than what they expect.

The article about expected returns covers a very limited time period. It may be right but on that limited evidence it doesn’t tell us much more than the predictions of bond bears. Most of the results it shows are likely because of the unexpected decreases in interest rates over the last few years. Do you know of any studies showing the long-term differences, similar to the expected returns you had in your recent post about various stock/bond allocations? I’m sure longer-term bonds have higher returns but I don’t know by how much.

@Richard: Choosing to avoid bonds because they don’t suit your investment objectives is perfectly reasonable. That’s just part of the usual asset allocation decision. Very few people have the discipline to hold an all-stock portfolio, but if you’re one of them, that’s fine. It only becomes a problem when people encourage others to make tactical moves based on their interest-rate forecasts, or when they ignore the risk of the alternatives they suggest (i.e. using dividend stocks as a replacement for bonds).

Based on the data available at Norbert Schlenker’s website (http://libra-investments.com/Total-returns.xls), from 1980 through 2013 Canadian short-term bonds returned 8.25% annually, compared with 9.30% for the “universe” and 10.54% for long-term bonds. (Staggering, I know, but 10-year GOC bonds yielded over 16% in 1982!) Long-term bonds do have higher expected returns, but with much more volatility. Most investors will find that short or intermediate maturities make a more appropriate core holding when they consider the risk/reward tradeoff.

I think the short-term bond fund makes sense for those who want to hedge against rising interest rates in the near future. At least the maturing low-yield bonds within the fund will be replaced with higher interest bonds.

I’m sure you get asked a lot about, not just bonds, but the overall market and whether now is a “good time to buy” based on current valuations. I looked back and found articles in 2011, 2012, and 2013 all declaring the market was too high and to wait for a correction before investing. The same articles also talked about what a disaster it would be to buy bonds.

It may not feel right to buy stocks or bonds right now, but as long as you have a long term approach in mind, and rebalance annually, you’ll be better off buying now than standing on the sidelines waiting for the perfect moment to jump in.

@CCP: Thanks, that’s a difference of a little more than 1% per year which can be very noticeable over a long time period. This shows up in the current yields too since long-term bonds show about 1.1% more than the universe index today. They will be more volatile, but if they’re still uncorrelated to the stock market that could work out well. Once again it’s something that’s only suitable for investors who are very comfortable with the added risk. For anyone who is the slightest bit uncertain about the risk they’re taking it’s better to have something they can live with in the worst circumstances.

Unfortunately, looking forward long-term bonds aren’t looking like a very neat asset class (financial advisors faint at the mention of them)! They have high risk, produce low returns, and so don’t provide much in the way of diversification unless one thinks interest rates in Canada will go lower (few do)! I’m thinking something like ZAG with its 30% long bond weighting is not ideal and that VAB is better if one were to choose starting out their portfolio or is average duration a better metric for a bond etf such that the 30% is not really significant?

Very interesting and fair. Market timing is something that I consciously avoid. But it is frankly tricky, at least for me … but I’m getting much better :) Perhaps like many people, I am opinionated and have views in regards the markets. I used to think that I could beat-the-market by cleverly picking fabulous stocks, sectors or asset classes … but in hindsight I perhaps remembered the winners more than the losers! And I was probably taking needlessly high risk. Humble pie. Thanks Dan (and also http://johncbogle.com – founder Vanguard) – please keep up the great work. And I’ll keep trying to resist temptation …

“The investor’s chief problem—and even his worst enemy—is likely to be himself,” once quipped the great Benjamin Graham.

http://www.etfguide.com/why-do-so-many-investors-self-destruct/

CCP: “I’ve long believed the most difficult part of being a Couch Potato investor is resisting temptation.”

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2013/12/30/the-failed-promise-of-market-timing/

@HarveyM: ZAG and VAB have very similar portfolios, with roughly 40-45% short-term bonds (< 5 years), 25% intermediate (5-10 years) and 30% long-term (10+ years). ZAG actually has a slightly lower average term (both are just over 10 years) and a slightly shorter duration (both are about 7.2). The average duration of a bond fund is a good estimate of its volatility, so I would consider these funds to be extremely similar.

on XBB performance page it shows -1.50%(NAV) annual return for 2013

@singh: Yes, that’s correct for the 2013 calendar year. The one-year performance shown above is for the 12 months ending June 30.

@CCP: I’m confused by the XBB returns. From your “Bonds, GICs and the Yield Illusion” article a passive investor must use the YTM of a bond fund…due to premium bonds…. That puts XBB at 2.5%. (I’d be better off with a ladder GIC.) Am I missing something?

@Brad: The YTM is a good estimate of the expected return of a bond fund, but it assumes interest do not change. In practice that never really happens, so a bond fund’s return is never knowable in advance. Over the last 12 months, for example, the return was 5%. During the calendar year 2013 it was negative.

A ladder of GICs may indeed provide a higher yield than a bond fund, but there is a tradeoff. GICs are not liquid, so you cannot sell them before maturity. They also have stable prices, so if interest rates do decline (as they have in the last year or so) you won’t get any boost in return. Unlike with a bond fund, the return of a GIC (and an individual bond, for that matter) is knowable in advance.

I also think short-term bonds make sense, even for long-term investing.

The key thing that comes to mind when I think of bonds (and fixed-income assets in general) is an act of “protecting against myself”. I’ve started to avoid bonds because I believe, at least for now, I’m comfortable with an all-equity portfolio (a mix of stocks and ETFs). I no longer feel I need the protection because I’m more comfortable with my investing approach and namely, my investing behaviour. The proof of this of course won’t be revealed until equity markets tank (again, eventually) and I’ll see if I can stick to my plan through some trying times. Monkeys picking stocks would have had a good run in the last 5 years.

Mark

Looking at this from a different perspective…

I agree with your points. But if you may be stuck in for example a work pension fund as many are where the return can be less then the management fee of the fund it would lose money every year. So in those cases if you have a gic option it may have been the way to go. Unfortunately not everyone is in a XBB like etf. For many it will have been a negative return.

@Mark: As you may know, we use only short-term bonds in our clients’ portfolios at PWL. This is true regardless of the interest rate environment: the idea is simply to keep volatility as low as possible on the fixed income side of the portfolio, especially given that the value/small tilt we use on the equity side (using DFA funds) can be more volatile than plain-vanilla cap-weighted funds. There’s no single way to manage a portfolio: there are many reasonable approaches. But guessing about interest rates isn’t one of them. :)

@Paul N: Well, it’s hard to disagree with the decision to avoid a bond fund where the management fee is higher than the yield to maturity. If that’s the case in your DC pension plan you may want to fire off a complain to your HR department because that’s highway robbery!

@MOA My advice to my adult children has been when beginning to invest start with no more than 50% equity allocation and then wait for a correction. This then will determine both one’s real life risk tolerance as well as flesh out one’s risk capacity which is important. If handled well (rare in my experience!), then increase the equity allocation. Our brains are programmed to sense short term fright situations (market crashes) with immediate flight! It’s a powerful reflex midbrain thing for self preservation and my observation is that few have the power to override with higher brain braking. May you be one of those few :). My own equity allocation consequently has never been higher that 40%!

Our portfolio of bond have actually been growing over the last few years. We follow a value averaging investment plan and with the run up in equities we find that any new money we have to invest goes directly into bonds/GICs. We don’t mind that there is some risk in the bond market, given the recent run up in the equities markets we find that there is risk everywhere now. Our asset mix is 34/66 Bonds/Equities at the moment and its shifting towards bonds as equities continue to rise.

I think that part of the problem is our perception of what are “normal” interest rates. Twenty or thirty years ago, you could make a good return without taking any risk. You just needed to park your money in GICs. Alot of older people are upset about the current “low interest” environment and are expecting rates to return to their previous historic highs. But if you look at a much longer time frame, the 1980s were an anomoly which we can’t expect to be repeated.

As an asset class decision, and a volatility dampening vehicle, bonds are fine even with very low yields.

That said, when we are dealing with yields in the 2-2.5% range, pre-tax (!), and pre-MERs (which granted are exceedingly low for some Bond ETFs), and inflation recently topping the BoC’s 2% target – it is clearly critical for investors to consider what remains in it for them… (On top of which – as you know – if said ETFs are held in a taxable account, there is this not insignificant issue of getting taxed on the cash on cash yield, which is meaningfully higher than the more relevant YTM measure…).

Not arguing against the gist of the suggestion Bond Bears should admit they were wrong, but certainly suggesting the “victory parade” from here on in needs to take all of these factors into account to properly inform investors about what their prospects are in taxable accounts, on an after everybody else’s needs and fees have been satisfied. Never mind, by the way, that while everyone, Gov, etc collect, the risk is all … for the investors!

@ Dennis E

Historically back to 1935 Prime rates have been above 5% on average. Yes the 1980’s were an anomaly, but certainly today’s rates are too. They are artificially held down and 6 or 8% being a rate could certainly be a reality again one day over just the next 5 years. I can’t remember a time ever in my lifetime where governments collectively have directed monetary policies like they do today. It’s a bit of a math experiment that could still go wrong and we could have a reactive swing the other way.

I’m glad my goal is to longer try and make money from all asset classes all the time. That’s not what diversification if about, right? Some years certain things will drop, some years they’ll rise. That one colour-coded chart I’ve seen (here probably?) proves it’s unpredictable. Anyone who thinks they know what’s going on must be a loon. A bonus of diversification–hanging onto the falling index funds is you’re continuing to buy at lows. As a Global Couch Potato (Option 2) I’ll gladly take the 2013 bond index drop of -1.6% for the overall return of 15.9%. BTW, I know that’s probably not a return reflective of long-term investing, but I still like parading that number around very much! (Especially when people who actively invest tell me last year was great and they made 9%.)

Even thought there’s always some “I’m a unique individual snowflake investor and things are different with me so please agree with my opinion”, things in the comment section here, I always appreciate the re-enforcement of the CCP main messages here, Dan.

Just wanted to run a strategy by you, Instead of bonds, if you use fixed deposits in emerging economies, which are government insured upto a certain amount, you could be earning upwards of 9% Rate of return while being exposed to country risk and FX risk. Rates taken from the following link http://www.deposits.org/world-deposit-rates.html

@Edward: Your comment raises an important point. Right now people see significant risk in both bonds (“rates could rise”) and stocks (“we’re overdue for a correction”). But if the past is any indication, it’s unlikely that both of these asset classes would get hit hard at the same time. When stocks plunge, bond prices tend to go up, and when interest rates rise it is usually because the economy is heating up. It’s all about balance.

@Da-Man: I’m not sure why (or even how) a Canadian would do that directly. And if you were inclined to do so, why not just buy an emerging markets bond ETF: there are hedged versions that mitigate the currency risk. Of course you would still be exposed to the country risk, which is why I would not recommend EM bonds as a core fixed income holding.

We’ve been nervous about our bond holdings for the past 3 years but there is no other fixed income choice in one of our DC pensions. Luckily when bonds crash they don’t tend to drop 50% so we’ve just gritted our teeth and waited. Last year the fund lost about 2% but it made it all back in January this year! And it’s been climbing since.

I’m not really sure that I trust what is happening “inside” the bond fund: they certainly aren’t just holding bonds to maturity. But since it’s our only choice, we’re holding tight.

Eventually we hope to get out of the bonds there by increasing fixed income elsewhere across our total savings, but it’s tricky because the equity fund choices are also not the ones we would want given a free choice!

I can’t say that I’m a fan of DC pensions….

@ B Crooks

Just to illustrate my point above as my DC plan choices sound like yours, what does your bond fund charge you in fees? So if you lost 2% you probably lost over 3% because you need to add your funds fees. To it. Probably 1 to 1.5 % additionally.

Unfortunately complaining to “”HR” is unrealistic as most workplaces won’t listen to you and in fact will single you out as a troublemaker for complaining. The fund manager in charge of the company DC fund will tell your HR and manager that it’s you that is wrong and feed them all the standard BS of how good a plan you are in and your safe with us and protected legally.

It hasn’t rained in two weeks, must be going to rain Monday then……

Flipping a coin and getting tails the past 15 times, chances are next flip I get heads…..

@EcoHeliGuy I’m not sure what point you’re making, but those examples are very different probabilistically. In the former, not raining for the last N days implies a higher likelihood of rain on day N+1, generally speaking. The latter is the Gambler’s Fallacy: prior coin flips are independent events that have no bearing on the latest flip. Neither seems especially relevant to the bond market.

@CCP, quite a while back I implement a tactical approach to bonds by reduced duration. I did this because I was worried about the interest rate risk. I am not sorry I did because it I can (still) sleep at night and I’ve given up almost nothing in terms of return (see below.)

When I made this decision, I had been closely following what different people said about bonds and I think you may be misrepresenting their views somewhat. In particular, yes, a lot of people have been saying for a while that long bonds look like a bad investment because of the interest rate risk. The most widely reported bond bear was Warren Buffet when he wrote in the 2011 Berkshire shareholder letter “Right now bonds should come with a warning label.”

For these bond bears to “admit” they were “wrong”, one has to ask what they were wrong about?Remember tactical asset allocation isn’t done in a vacuum, it’s just a bias to an otherwise neutral portfolio. What were the overall portfolio recommendations these tactical asset allocators were giving? The most common answers was to reducing bond holdings and increase stock holdings (what Buffet recommended for long term investors) or to reduce bond duration or both (what a lot of other commentators were saying and what I believe funds like the Mawer Balanced Fund did.). The less common answers were to increase corporate bond holdings or even to use a mix of short term bonds with some high yield bonds.

Using the Stingy Investor tool, I ran the scenarios I could with it for the last 5 years and calculated the average annual rate of returns for each.

Global Couch Potato 9.6%

Global Couch Potato but replace All Bonds with Short Term Bonds 9.0%

Global Couch Potato but reduce bond holdings to 30% and increase stocks to 70% 10.4%

Global Couch Potato like above but using Short Term Bonds 9.9%

I couldn’t run them, but by looking at the iShares site, it looks like the other strategies of using short term corporate bonds possibly with a mix of high yield bonds would have worked well too.

So depending on how you look at it, ALL these “tactical” moves actually worked great and the tactical allocators were not wrong at all. All scenarios they recommended have worked out well and met their goals. E.g. the ones holding short duration bonds reduced the interest rate risk while still having a good return and the ones with a tactical bias towards stocks had higher returns.

@BrianG: I can’t tell you how many times I have heard people over the last five years that interest rates have “nowhere to go but up” and that bonds were all but guaranteed to lose money. These predictions were dead wrong. The tone was not usually “short-term bonds may have lower expected returns, but they also have less interest rate risk.” It was closer to “why would anyone buy a broad-based bond fund when it is sure to get killed?”

Suggesting that bonds are more risky than stocks (see the Globe article linked above) was also irresponsible, even though anyone who loaded up on stocks over the last few years was rewarded for it.

That does not mean it is a bad idea to use short-term bonds: indeed, the ones we build at PWL use short-term bonds as a core holding simply to reduce volatility. The problem is thinking you know where interest rates are headed and that you can reliably achieve better results by shortening and lengthening duration based on those forecasts. My goal here is, as always, to argue that investors who think they are smarter than the market are likely to be humbled. I believe it’s better to pick an asset allocation appropriate to your situation and stick to it with discipline.

@CCP, it’s starting to sound a little too dogmatic vs. fact based when you dismiss the numbers or dismiss what the biggest bond bear actually said.

Your headline screams “Bond Bears: Admit You Were Wrong”. By making this bold claim, the onus is on you to show they were wrong based on what they said. Read Buffet’s 2011 letter to see what he actually said; it’s online. Fact is, if you took his advice, adapted it to your situation you would have done well as I have shown. You can claim this was blind luck and I can equally claim it was blind luck that bonds did as well as they did without running into a major downside event. Either may be true, but I don’t think there is enough unbiased evidence to support your claim that the biggest bond bear was “wrong”.

It is a fact that long government bonds have these problems: low interest rates, low current inflation, government intervention (buying) which is suppressing rates, government money supply intervention (increasing it). It’s pretty hard to argue that this cannot go on forever and that at some point one of these factors will change and bang, long bonds will take a big hit or that they won’t keep up with inflation. A negative double digit percentage hit in real terms is very possible if history any guide.

Review the U.S. SPIVA Reports for 2012 and 2013 (after Buffet made his comments) which show that active fixed income management did very well over the last few years. I would argument this is possible right now because of the current level of government intervention has made the market inefficient. (Which many also argue have propped up the equities markets.)

So, I do believe it is foolish to hold long (or even medium) duration bonds right now until the unprecedented level of government intervention stops. Given the current yield curve the upside potential vs. risk is just not worth it. It’s not about predicting the future with certainty or trying to time the market, it’s about managing risk. Even you’ve admitted it with regard to what you actually do at PWL vs. what you say to do on this website with your model portfolios. (Aside: The fact that what you say in your model portfolios on here and what you do are different is troubling, but I will leave that to your readers to process.)

Most troubling of all, I believe that this article may make some investors overconfident and not fully consider the downside risk of medium to long term bonds right now. Until government intervention stops messing with the market, for most people, I believe the core bond holding should be a short term one (like you do at PWL) and that it is somewhat reckless to suggest otherwise given the current situation.

Maybe a article can be written on preferred shares for the fixed income part of a portfolio?

They pay about 3 percent more and are not as volatile as common share.

I find them complex to understand and don’t understand the true risk with them and I am sure others would like to use them were appropriate?

Thanks.

@mark: I have no real expertise on preferred shares, so I don’t feel qualified to say too much. I will say that we do not use them with our clients: we prefer to keep fixed income investments as safe as possible, and preferred shares are at least as risky as corporate bonds (witness their performance in 2008). That said, I think one can make a reasonable argument for using them as an alternative to corporate bonds in a non-registered account. They can be quite illiquid and complex if you’re buying individual prefs, so for most people an ETF is the way to go.

@mark, preferred shares are definitely not fixed income and should never be compared to it. For instance, I suggest you chart the total return of CPD and XBB and see for yourself. I use txmmoney.com to make these charts… turn on “adjust for dividends and splits” to compare total returns.

You will find that preferred shares sink with the stocks when stocks plummet (e.g. 2008) and sink like bonds when interest rates rise. The worst of both worlds!

Also, try reading the prospectus for a typical preferred share. They are often very complex, customized and not written in the favour of an investor which makes me run the other way. This is unlike bonds and common stocks which have more standardized legal rights.

I personally wouldn’t touch them. Why not just stick with a plain Couch Potato Portfolio and adjust the percentage of bonds to match what suits you?

I peripherally related/Noobie question on bonds. If maturation date for XBB say is 10 years, and one looks at the change in bond recommendation on GlobCouchPotato to VAB, would there be any penalty in selling XBB before that 10 years? or can it simply be viewed as a stock where loss or gain of share depreciation or appreciation existed in that time frame from purchase to sell?

@lucas: Good question. It’s not accurate to say that a bond fund like XBB has a “maturation date.” The average term of the bonds in XBB is about 10 years, but the fund is managed in a way that keeps that exposure more or less constant. In simplistic terms, it’s a bit like buying a 10-year bond today and then selling it next year to buy another 10-year bond, and repeating that process indefinitely. So the fund will never mature the way an individual bond will.

There is never a “penalty” for selling a bond ETF, but it is certainly possible that if you sold it a year or two after purchasing it then you could receive less than you paid for it. If interest rates have gone up during our holding period, the fund would have fallen in value.

This may help:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2011/07/07/holding-your-bond-fund-for-the-duration/