Monday’s post about factor analysis was, I admit, too technical for most readers’ tastes. At least that’s the conclusion I drew when the two most enthusiastic comments came from a professor of statistics and an astrophysicist. But the brave few who managed to read to the end saw my promise to put all this in context. What can factor analysis teach us about where an ETF’s returns are really coming from?

Two decades of research has shown that the returns of a diversified equity portfolio can largely be explained by its exposure to three factors: the market premium, the value premium, and the size premium. A broad-market index fund like the iShares S&P/TSX Capped Composite (XIC), by definition, should be neutral in its exposure to the value and size premiums. And as we saw in my previous post, it is: the value and size coefficients for XIC are negligible. So, on to the next step.

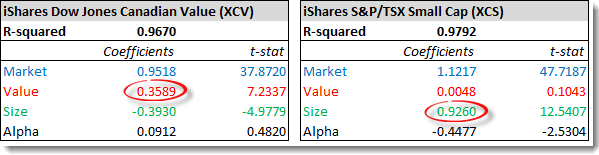

Let’s now take a look at the iShares Dow Jones Canadian Value (XCV) and the iShares S&P/TSX Small Cap (XCS). We should obviously expect XCV to have extra exposure to the value factor, while XCS should capture the size premium. Here are the results of a factor analysis covering the five years from 2008 through 2012:

Turns out XCV does indeed show a significant value tilt, with a value coefficient of 0.3589. To put that in context, during a period when value stocks outperform growth stocks by 2%, this fund would be expected to outperform the market by about 0.72% (0.3589 x 2%).

On the other hand, the fund’s size coefficient is significantly negative. That’s not surprising considering the Big Five banks make up almost 40% of its holdings. During a period when small caps outperform large caps by 2% you would expect XCV to underperform the market by about 0.79% (–0.3930 x 2%).

Moving on to XCS, we see the fund has a predictably huge small-cap tilt, as shown by its size coefficient of 0.9260. The only surprise here is the fund’s negative alpha—and a pretty high one at that. Management fees will have some impact here, but they’re not enough to account for a drag of 0.4477% per month. Unfortunately, when a factor analysis shows negative alpha we know something is causing a drag on returns, but we can never be sure what that is.

An eye for value

OK, it’s time to look at some other popular Canadian ETFs and see what we can learn from factor analyses.

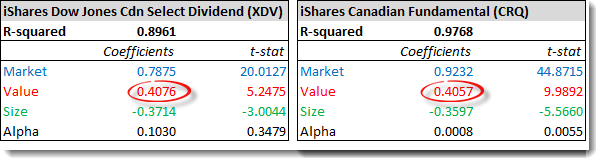

Over the last five years, dividend stocks have tended to outperform the market: for example, the iShares Dow Jones Canada Select Dividend (XDV) delivered an annualized 3.76% from 2008 through 2012, compared with 0.58% for XIC. Meanwhile, those who champion fundamental indexing have noted it too had good record over this period: the iShares Canadian Fundamental (CRQ) returned 2.46% annually. Let’s see what a factor analysis reveals:

What do you know? Both ETFs show an even larger value tilt than XCV. As Justin Bender argued on his blog last year, dividend ETFs can be thought of as “value ETFs in disguise.” (Larry Swedroe goes into more detail on this subject here.) Think of it like this: a stock’s yield is its dividend amount divided by its price. Many dividend junkies focus on the numerator in that fraction (the high dividend amount), but the real driver of the returns is the denominator: the lower price.

Fundamental indexing, too, is really just a methodology designed to get greater exposure to value stocks, something its critics have long noted. Research Affiliates, creators of the fundamental index, downplayed this for long time, but now they seem to acknowledge it freely.

During the five years ending in 2012, the iShares Dow Jones Canadian Value (XCV) returned 2.93% annually, falling between XDV and CRQ. That’s not a coincidence. All three funds are just different ways of tapping into the value premium, which was strongly positive during these five years. When the value premium is negative during other periods, you can probably expect these funds to struggle in similar ways.

Special FX

Now onto a fund that’s more of a head scratcher. The First Asset Morningstar Canada Value (FXM) has been the best-performing Canadian equity ETF during the last year: over the 12 months ending September 30 it returned almost 29%, while the broad market was up just 7% and the three value funds above managed “only” 16% or so. How did FXM pull off that remarkable performance? Have the folks at Morningstar found a way to harness the value premium in a way no one else has ever managed?

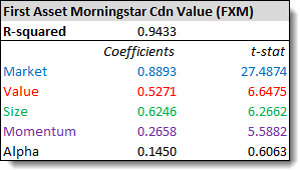

We can’t look at five years of fund performance, because FXM was launched in February 2012. However, First Asset kindly provided us with monthly index data to fill in the gaps back to the beginning of 2008. This time the factor analysis yielded some surprises:

Yes, there’s value tilt, but there’s also a huge—and statistically significant—size tilt as well. (Remember, in the three value funds we considered above, the size coefficients were negative.) There’s also a significant alpha, though the low t-stat indicates it may just be random noise. But however you slice it, FXM is more than just a value fund.

We decided to dig a little deeper. Though it’s notoriously difficult to harness, there’s lots of evidence for a fourth factor: the momentum premium. Stocks that have recently risen or fallen in price tend to persist in the same direction for some time. So we ran a new regression with this fourth factor thrown into the mix:

This definitely helped: the higher R-squared value suggests the data fit this model better than our three-factor analysis. Momentum does indeed seem to contribute to the excess return. (In the Morningstar index tracked by FXM, one of the criteria is three-month earnings estimate revisions, which is a traditional momentum screen.) The value coefficient is higher now, too, but the size coefficient is still unexpectedly large.

Nathan Stretch—the reader who first encouraged us to look at FXM—ran his own regressions using different factor data and found even less evidence of value exposure and even more unexplained alpha. The truth is, it’s hard to know what’s going on here. FXM certainly has a very different sector mix: while the three value ETFs above are dominated by the Big Five banks, FXM includes exactly none of them. If the fund were actively managed, you might attribute some of its outperformance to stock-picking skill. Since it’s not, it may just be luck.

Bottom line, FXM bears no resemblance to the other value funds we’ve considered here. While its recent performance has been outstanding, it’s hard to know whether it will continue, since it’s not clear where those outsized returns are coming from.

Note: Once again, thanks to Justin Bender and Nathan Stretch for their help with these factor analyses. If you’re interested in learning how to “roll your own,” see Justin’s new blog post, How to Run a 3-Factor Regression Analysis.

@Nathan: Maybe I misunderstand, but I was thinking in terms of rebalancing the funds, resulting in buy low sell high as a benefit, as we do between the stock and bond allocations of the portfolios, e.g. in 2001 small value gained 40%, so some of that fund would be sold and S&P (which went down 12%) purchased to rebalance and so on. Am I missing something here?

@Tristan: Maybe CCP can explain this better, but for the most part the “rebalancing bonus” just removes the disadvantage of holding multiple funds, rather that giving some additional bonus. In precise terms, it brings the “compound annual growth rate” of the portfolio closer to the arithmetic average of its returns, by reducing the volatility of the combined portfolio to less than that of its constituent parts. If you can get equivalent exposure in a single fund instead of many, this advantage is built-in. It’s like having a portfolio that rebalances itself continuously.

This is similar to holding VXUS instead of separate funds for Europe, Asia, and Emerging Markets. Its also one of the advantages of broad-market, cap-weighted index funds.

Now, there is some evidence that due to mean reversion you may actually receive some additional benefit from rebalancing less often – say every 1-2 years – rather than continuously, as you effectively do by holding a single fund. So there may be *some* benefit to holding multiple funds in place of one, but I doubt it outweighs the added costs and complexity.

Larry’s situation is a bit different though, because he’s not looking at multiple funds instead of one, he’s just looking at 4 funds instead of 3, and by using 4 funds he can hold the same amount of each, making rebalancing simpler. So again, I expect the portfolio is designed that way for simplicity rather than to capture a very hypothetical bonus by holding more funds.

@Nathan: I see now. That’s quite clear. Now I understand why, for US equity, you have 60%VBR and 40% VTV. You are getting the amount of small and value tilt you want with only two funds. Thanks again for your detailed explanations!

The math supporting factor investing is very compelling, and I have no doubt that it could add real returns if implemented well. The concern I have is with respect to “operationalizing” the model. Specifically, can we reasonably expect the benefits of targeting factors to outweigh the costs for retail investors?

MERs seem significantly higher for factor oriented ETFs than cap weighted or whole market ETFs. Perhaps more importantly, factor oriented ETFs seem to have quite high turnover (Momentum > Value > Small). In taxable accounts, this activity could lead to meaningful taxation. The transaction costs for small cap shares is probably quite high, and this is opaque to retail buyers of a small factor ETF.

I find the concept of a 3 factor model for allocation to be very appealing, but at what point do these costs outweigh the benefit? I wonder if those here actually using factor based strategies could comment?

@William: Great question. This has always been the challenge: once we identify a premium in the market, how do we capture it in a way that provides a benefit after costs and taxes? It’s difficult, and that’s the main reason I generally favour plain-vanilla cap-weighted indexes. They are not perfect, but they reliably capture the equity premium with trivial cost and turnover.

The premiums offered by small-cap and value stocks are not likely to be huge, so you need to keep costs low to get any meaningful benefit. I don’t know what the number might be, but let’s say 0.5% or so. Dimensional Fund Advisors probably does the best job in this area: their costs are very low and their approach to capturing the small and value premiums minimizes turnover and plays attention to tax management. With momentum, many people believe it’s impossible to capture over the long-term because of the excessive trading and timing involved.

@William costs and taxes are certainly a concern. I dug into some of those same issues a couple years ago, and concluded that it was still possible to find good opportunities in the US and EAFE, but that tilted Canadian and emerging funds likely weren’t worth the cost. (At least, at that time.)

I detailed my process in this wiki article (and the forum posts it links to) If you’re interested: http://www.finiki.org/wiki/Multifactor_investing_-_a_comprehensive_tutorial

(I certainly don’t think it’s necessary for a person to go to that much effort, but you could always choose to estimate more and not get into every detail. One quick way to get started, for US funds at least, is this site, which will take care of the factor analysis for you: http://www.fundfactors.com/ )

@ CCP – thanks for your response to what I now realize is an older thread. This site is outstanding and has confirmed a lot of my previous thoughts about how to approach investing. In my opinion this is one of the best investing sites available. I like the DFA funds, but wish there was a way to buy them without an advisor!

Hi Nathan, thanks very much for your links. I have previously read your Finiki article – it’s excellent. I have played around on the FundFactors site a bit too. I have even done a little bit of regression modelling around this… Do you control for covariance between factors in your analysis? I wonder now that factor investing is becoming trendy (witness all of the new funds popping up) whether the premia associated with recognized factors will diminish. I suppose the worst that would happen is that small and value would just get turned into beta.

Ah, cool. IMO the factors already represent beta, just different from market beta. For that reason they shouldn’t disappear in the long term, although obviously they will sometimes underperform short term, perhaps even due to being ‘oversold’. People have been predicting that for decades now though. Like the market itself, imo timing is impossible.

As far as covariance, I don’t think there’s a need to explicitly consider it. For intentionally chose these factors over orthogonal ones because they’re linked to real world characteristics. They don’t have more or less descriptive power than a set of independent factors. If you’re thinking in terms of optimal diversification, I guess you could consider it. I posted a chart of correlations between factors in different geos on bogleheads somewhere – search my posts for ‘correlations’ – but honestly they shift so much I doubt it’s worth it.

@CCP:

“I don’t know what the number might be, but let’s say 0.5% or so. ”

I take it that your “0.5% or so” is your guesstimate of the small cap/value return advantage averaged over decades. If this is the case, looking at the Canadian equities market, considering that plain vanilla TSX ETFs now cost 0.06% annually to hold versus 0.50% to 0.60% for small cap/value, assuming that the “guesstimate” is reasonable, it is hard to make a case for the payoff on the extra work involved in managing a Canadian Equities “Uber-Tuber” type portfolio. Is the math actually as straightforward as I am making it?

A further thought about the premia associated with factors. When we say that the premium associated with a factor, let’s say value, does this assume a combined long-short strategy? The value factor in the FF 1992 paper is “HmL” – literally, “high minus low”. As long only investors, are we only getting the “L” portion? This might imply that the factor premium is much smaller. Similarly, for size (“SmB” – small minus big), if we go long S but don’t short B, do we get only half of the FFF premium?

I got this sense from the original papers, but don’t see this outlined in most of the discussions of factor investing. Presumably, this is because I am missing something that is blindingly obvious to everyone else…

@William: I don’t think this is obvious at all, and it’s frequently misunderstood. You are indeed right that the FF premiums are based on long-short portfolios. So a fund that simply had an added tilt to small or value should not be expected to capture the entire premium.

An update on FXM covered above…since inception (Feb. 2012) return as of October 31, 2014 was 16.6%. TSX Composite returned 9.5% over the same period.

@Oldie, hi again.

Justin Bender of PWL kindly publishes informative statistics (including normal/value/growth and across various time periods) at http://www.canadianportfoliomanagerblog.com/market-stats/. Interesting data and certainly relevant to your question. In my view, it appears that the historical outperformance of canadian value indices, relative to whole market, does not appear significantly higher than the variance in difference (as you suspected). But, looking forwards, the incremental fees are guaranteed and the outperformance rather less so.

Whether the addition of a value ETF to a portfolio with significant TSX Composite exposure reduces risk, through sector diversification, certainly seems plausible to me. But the overall potential benefit strikes me as underwhelming. Perhaps more practically, if this is a significant concern for you then I tip my hat and say well done! … as there seem plenty of other topics (portfolio allocation, right accounts, savings rate, rebalancing, …) of materially greater impact.

@CCP, I wonder if you’ve updated your conclusion/thoughts on FXM? Or indeed the source of its then over performance.

“Bottom line, FXM bears no resemblance to the other value funds we’ve considered here. While its recent performance has been outstanding, it’s hard to know whether it will continue, since it’s not clear where those outsized returns are coming from.”

@Ross: I haven’t looked at FXM closely since writing this post, so I don’t have anything useful to add.

@CCP Dan, given the passage of time, I wonder if you have changed your thought on FXM? If one were to hold 20% CDN in their portfolio, would a strategy such as having 10% VCN 10% FXM long term make sense?

@Grim: I don’t recommend using any “smart beta” ETFs. I suggest sticking to traditional index ETFs for the whole portfolio.