Investors are hungry for success stories, especially tales that include high returns with low risk. And the investment industry is always happy to stoke that appetite.

One of the most popular stories today is the so-called All Seasons portfolio, whose virtues are trumpeted in the massive bestseller Money: Master the Game, by motivational speaker Tony Robbins. The book has been out since last November and I thought the hype would blow over quickly, but I’m still getting inquiries about it, so I thought I’d take a closer look.

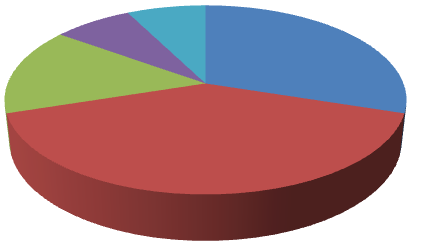

The All Seasons portfolio was created by Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates, one of the largest hedge fund managers in the world. It’s based on Dalio’s similarly named All Weather fund, which reportedly has more than $80 billion USD in assets. The portfolio has the following asset mix:

30% Stocks

30% Stocks

40% Long-term bonds

15% Intermediate bonds

7.5% Gold

7.5% Commodities

In a backtest covering the 30 years from 1984 through 2013, the All Seasons portfolio had an annualized return of 9.7% (net of fees) and only four years with a loss. Its worst year was a modest –4% in 2008. With a risk-return profile like that, it’s no wonder so many investors have been attracted to the All Seasons portfolio. In fact, a service run by Robbins’ own advisor has been swamped with requests from investors who want a piece of this seemingly miraculous strategy.

So, is the All Seasons portfolio really a recipe for stellar returns with minimal risk? Or is it just another example of investors chasing hypothetical past performance?

The reasons for the seasons

The All Seasons portfolio is based on the idea that asset prices move in response to four forces: rising economic growth, declining economic growth, inflation and deflation. In each of these economic “seasons,” some asset classes thrive and others suffer. For example, when growth is strong and inflation is low, stocks are likely to perform well, whereas commodities and gold benefit from rising growth and rising inflation. Bonds do well when economic growth and inflation are both falling. By including all of these asset classes in your portfolio, you’ll do well under all conditions. It’s like travelling with sunscreen, an umbrella, a swimsuit and a parka.

There’s nothing wrong with this general idea: most investors understand that a portfolio should include asset classes with low (or even negative) correlation. Nor is it an original thesis: it’s very similar to what Harry Browne wrote in the early 1980s. Browne’s Permanent Portfolio was also based on the principle that you should hold asset classes that would thrive during four economic scenarios: stocks for prosperity, cash for recessions, gold for inflation protection, and long-term bonds for deflation.

Was the performance really remarkable?

But while the premise of the All Seasons portfolio is reasonable, there’s nothing astonishing about its performance during the last 30 years. Moreover, anyone expecting it to deliver 9.7% with low risk in the future is likely to be disappointed.

The returns were unremarkable. A 9.7% annualized return doesn’t mean much unless you compare it to the alternatives. The truth is that all diversified portfolios performed well during the last three decades.

Despite the carnage of the dot-com bust at the turn of the millennium and the financial crisis of 2008–09, most of those 30 years were extremely kind to stocks. Late 1987 to the spring of 2000 saw the longest bull market in history, and the one we’re enjoying now ranks third all-time. From 1984 through 2013, the S&P 500 returned a whopping 11.1%.

And what about bonds, which make up 55% of the All Seasons portfolio? In the US, long-term government bonds returned 9.4% during the period. In Canada, they did even better: the FTSE TMX Canada Long-Term Bond Index returned 10.3% over those 30 years.

Once you consider the context, a 9.7% annualized return since 1984 isn’t remarkable at all. Anyone who stayed invested in a diversified portfolio would have seen similar results.

The risk was not “extremely low.” OK, maybe the returns of the All Seasons portfolio were in line with a traditional balanced portfolio, but risk was much lower, right? In an article for Yahoo Finance, Robbins reports that the standard deviation of the portfolio during the 30-year period was 7.63%, which he declares is “extremely low risk and low volatility.”

I’m not sure investors would agree with that assessment. If a portfolio has an average expected return of 9.7% and a standard deviation of 7.6%, that means in 19 years out of 20 its annual return can be expected to range between –6% and 25%. That’s not “extremely low volatility”: it’s about the same as that of a traditional balanced portfolio. In our white paper Great Expectations, my colleague Raymond Kerzhéro and I found that a portfolio of 40% bonds and 60% global stocks had a standard deviation of about 7.8% over a similar period (1988 to 2013).

What about the fact that the All Seasons had only four negative years, all with only modest losses? Robbins and Dalio frequently compare the All Seasons portfolio to the S&P 500, which certainly saw much larger and more frequent drawdowns. But this is a totally inappropriate benchmark, as the All Seasons portfolio includes just 30% stocks. Dalio’s portfolio holds 55% bonds, which are far less volatile than stocks. More important, bonds only lose value when interest rates rise, and from 1984 to 2013 the yield on 30-year Treasuries fell from over 11% to about 3.5%. Any bond-heavy portfolio would have seen rare and modest drawdowns during that period.

There were many disappointing periods. The long-term returns of almost any diversified portfolio look impressive, but unfortunately you can’t buy 30 years of performance in advance: you have to earn those returns by doggedly sticking to your plan even when it disappoints. And let’s be clear: the All Seasons portfolio would have tried your patience many times.

While the portfolio never suffered huge losses, it would have significantly lagged a traditional balanced portfolio during the many periods when stocks delivered double-digit returns. That’s why this strategy—and the Permanent Portfolio, for that matter—had few followers during the 1980s and 1990s. A portfolio with just 30% stocks would have been met with derision during that long, giddy bull market.

Gold would have been even harder to hold. Sure, it glittered during the most recent financial crisis, but during the 21 years from 1984 through 2004, the real return on gold in Canadian dollars was –2.3% annually. Would you have had the guts to hold it through two money-losing decades?

Don’t make the mistake of thinking it’s easy to stick with a strategy when it underperforms during strong bull markets, as the All Seasons portfolio is almost certain to do. Bridgewater’s own All Weather fund returned –3.9% in 2013, one of the best years for stocks in recent history (the MSCI World Index was up almost 34% in Canadian dollars). My guess is that Dalio’s clients took little comfort in the fact that the strategy performed well in historical backtesting.

Couldn’t stand the weather

My goal here is not to beat up on the All Seasons portfolio specifically: on the contrary, I wanted to show that in many ways it’s not fundamentally different from other balanced portfolios.

My concern is that the All Seasons portfolio is presented as a magic formula that will dramatically outperform a traditional stock-and-bond portfolio with far less risk. The very name implies that it will perform well during all market conditions. But that wasn’t true over the last 30-plus years, and it’s even less likely to be the case during a period of low interest rates. (No one knows where rates are headed, but it’s absurd to expect 9% or 10% returns on bonds when yields are 1% to 3%.)

A well-diversified, low-cost portfolio executed with discipline offers your best chance of enjoying market returns with moderate volatility. But there’s no secret recipe, no optimal asset allocation, and no reward without risk. Be skeptical of anyone who suggests otherwise.

“A well-diversified, low-cost portfolio executed with discipline offers your best chance of enjoying market returns with moderate volatility. But there’s no secret recipe, no optimal asset allocation, and no reward without risk. Be skeptical of anyone who suggests otherwise.”

Very well said, Dan.

Hi Dan,

Thanks for this post. I was actually one of the people that sent you an email requesting your opinion on this this type of portfolio.

If you read Tony Robbins’ book you’ll notice that he repeatedly quotes Warren Buffett, I believe, who says “the #1 objective in investing is don’t lose money. The #2 objective: see objective #1”. I think that, for most unsophisticated investors, it is hardest to stick to their portfolio when they lose money. It is easier to stick with a plan if you’re making 7% when “the market” makes 9% (“at least I MADE money”). However it is much harder to see your portfolio decrease by 20-25% even though “the market” lost 30-35%.

For me personally, I would probably stick to one of your suggested portfolios. But my wife HATES losing money and really doesn’t understand or cares to learn how the market behaves. Therefore in my case it would be much easier for me to explain to her why losing only 4% instead of 20% during the 2008 collapse warrants us sticking to the plan.

From a Canadian perspective, I would take the 30% stocks and separate them even further into 10% Canada all Cap (VCN) and 20% All-world excluding Canada (VXC), so the portfolio would look something like this:

40% ZFL

15% ZFM

7.5% CBR (I have not really found an unheadged equivalent)

7.5% CGL.C

10% VCN

20% VXC

Thoughts?

@Daniel: Glad you followed up. You’ve actually hit on the exact issue I was concerned about. As I tried to explain in the post, the primary reason the All Seasons portfolio didn’t experience big losses was that it is loaded with long-term bonds, which performed extremely well over the period Robbins examined. It is mathematically impossible for that performance to be repeated, and there is no reason to believe this portfolio won’t suffer losses, perhaps significant ones. If interest rates rise, long-term bonds will be the hardest hit.

There are lots of investors who hate losing money, and that’s fine. The problems occur when people think they can avoid losses and still earn 7%. Clearly many people believe this portfolio offers that opportunity: it does not. A very risk-averse investor should consider a ladder of GICs for most of their portfolio. Yes, the returns will be low, but there is no way to earn higher returns without accepting some risk of loss.

I hear that Warren Buffett quote all the time, too, but it must have been taken out of context. If he truly meant you should never buy an investment that could fall in value he would never have bought a stock. Don’t forget that Buffett has also said (and I’m paraphrasing) that if you are not prepared to lose half your money you should not invest in stocks. That advice is much more realistic.

Interesting, but anything that comes out of the mouths of motivational speakers needs to be taken with a grain of salt. That said, if you diversify enough, losses will certainly be minimized, as will gains. As time goes by, I’m starting to think (as demonstrated by the 20 year annualized gains on the CCP Model Portfolio’s) that you always end up at around 6% – 7%. Main thing is to keep fees low.

Any idea what the MER on Robbins’ fund is? As Jack Bogle says, “You get what you don’t pay for.”

Another really good article (and ditto the earlier ones on the PP). Initially the PP seemed to offer better risk-adjusted returns than most others out there, until you realize that much of its advantage stemmed from the massive performance of Gold during the 70s/after decoupling from the dollar – an event that is surely not likely to be repeated. Similar to the case of LT Bonds and the AS Portfolio, if you dial out that event and period, the risk-adjusted returns of the PP are not significantly different than anything else.

Mebane Faber’s latest “mini book” actually looks at 7 or 8 “famous” portfolios and backtests them all. Despite massively different compositions, the conclusion is that they all performed within 1-2% CAGR over decades. Moreover, he notes that implementing what was in hindsight the best performing portfolio at a high cost results in worse performance than implementing the worst performer at a low cost! Therefore it’s likely more productive to focus on cost than on tweaking asset mix.

@Luc: I should be clear that the portfolio was not created by Robbins: it was created by Ray Dalio and popularized in Robbins’ book. The cost of implementing this portfolio would depend on the specific ETFs you choose.

@Willy: Thanks for the comment. I just ordered Meb Faber’s book, which sounds interesting. Perhaps not too surprising to hear that cost was the key factor in his analysis. There is a strong tendency to dwell on the minute details of a portfolio (I used to do it, too), but eventually you realize that as long as you are broadly diversified, keep costs low and execute with discipline you are likely to do well, whether you hold 7.5% in commodities or not.

@ Willy. Thanks, I might look into this book. I fantasize about 100% VXC, since I don’t plan on ever selling.

When I saw that allocation of long term bonds I had the same reaction… what about the asymmetry of interest rates approaching zero? I’ve been favoring short term bonds and GIC ladders for this very reason.

If I had to guess this portfolio’s results going forward (and I probably shouldn’t), it might range from modest under performance to outright bad.

Yet another example of why good investors develop a solid plan based on their level of risk and stick to it.

You can get a free copy of Mebane Faber’s latest book “Global Asset Allocation”.

He asks that you do a review on Amazon after you have read it – that is the only condition of getting the free copy.

Actually his last 3 books (electronic versions) were all free on Amazon.com last week. He puts them on for free occasionally and if you check his web site regularly, you can take advantage of the opportunity when it arises.

As Willy said – Faber covers several portfolios and concludes that the portfolio you choose does not matter much. The costs are the most important factor.

If you could know which portfolio would perform best into the future, high costs would turn the best performing portfolio into the worst over the long term.

Here is the link to request it for free.

http://freebook.mebfaber.com/

Because I was curious, I went to a website called portfoliovisualizer (no affiliation) and punched in this portfolio (ASP) along with the Permanent Portfolio (PP) and a 40/60 stock/bond portfolio (CP) and analyzed them from 1972 to 2014. Anyone can do the same to check my numbers.

The results I got were:

CAGR: 9.7% 8.9% 9.1% respectively

Stddev: 7.7% 7.8% 8.9%

Max Drawdown: -3.3% -5.1% -11.8%

Sharpe Ratio: .6 .5 .5

US Mkt Corr: .6 .3 .9

Int Mkt Corr: .4 .3 .5

Observations:

– 1974, 1979, 1980, 1981 all had annual inflation rates well over 10%. Be wary when these years are not included in historical returns for a magical portfolio because these were some tough years. Inflation adjusted returns in those tough years respectively were:

ASP: -11.0% 4.8% -2.1% -11.2%

PP: 1.7%, 23.0%, 0.9%. -12.9%

CP: -17.1%, -2.7%, 1.8%, -6.1%

– 2008 was a tough year for most portfolios. Inflation adjusted returns were:

ASP: -3.1%

PP: -2.1%

CP: -11.8%

Conclusions:

– ASP: looks like it was optimized by back testing for this time period. Over optimization can lead to a brittle portfolio is very unlikely to return similar results again. (As Dan has pointed out regarding LT bonds.) Also, it didn’t do that well in most high inflation years.

– PP: Simple allocation; likely robust in future. Lowest correlation with US and Int. stock markets; did well in high inflation years but not all (1981), did well in 2008.

– CP: Simple allocation; likely robust in future. Did poorly in high inflation years; did poorly in 2008, high max draw down

I could see someone rationally arguing for any of them or some variant (e.g. replacing long bonds with shorter term bonds today.)

Pick your poison. Personally, the PP attracts me because of its low correlation with both US and international markets. It’s almost hedge fund like.

That said, full disclosure, my own portfolio looks more like the PP without gold right now. I got out of gold in 2013. I have been thinking of rebalancing back into the PP with gold again. Gold works on very long cycles though… so we’ll see.

@Willy wrote: ” the risk-adjusted returns of the PP are not significantly different than anything else.”

Dive deeper and be wary of rolled up statistics that hide the details.

Please review my previous post. I believe that the PP has shown it’s behaviour to be different than most other portfolios in the following ways:

– very low correlation with US and International stock markets (0.3); getting a correlation this low without active management is not easy; this is a hedge fund like property (if you don’t believe me try getting below this with the same return/risk using portfoliovisualizer)

– it has shown itself worthy well beyond the initial dollar-gold break by Nixon in 1971. e.g. in 1974, 1979, 1980 it beat inflation unlike most portfolios; then it kept plugging along right through the crash of 1987, the dotcom bubble, and then took off in the 2000’s right thru 2008 to 2012. After that long run there was a blip in 2013, but it recovered in 2014.

– while you may say that the dollar-gold break along with floating exchange rates was a one-time event in 1971; I argue that both are an ongoing new; persistent reality until we switch back to a gold standard

If you can show me another portfolio that has similar or better characteristics to the PP, I’d love to know about it. I’m always open to new ideas.

@Brian G

I agree there is something special about the PP.

Two links I like going back to from time to time are:

————-

William J. Berstein’s take on the PP:

http://www.efficientfrontier.com/ef/0adhoc/harry.htm

Meb Faber looks at how using his timing method (checking the 200 day SMA once per month) can improve the PP:

http://mebfaber.com/2010/10/28/timing-the-permanent-portfolio-and-ivy-swensen-arnott-bernstein/

————-

And on the timing theme – from July 7 – US stocks are the only thing you would still hold if using Faber’s timing method:

http://mebfaber.com/2015/07/07/trend-review-last-man-standing/

Further to BrianG’s mentioning the Portfolio Visualizer site, I gave it a bit of a test drive, and while somewhat off topic, thought I’d post a link to this hypothetical “allocation”. I use quotes, because it’s not really an allocation when you’re 100% in one or the other, and not really much of a Couch Potato type of approach either.

Long story short, it’s swapping in and out of 100% stocks and bonds on a 12 month SMA. Probably not exactly a revolutionary or new strategy, that said, that blue line (logarithmic) is kinda straight.

US Vanguard funds are used since they have a longer period of inception.

The sample data is kinda small (1988 onward), and I was wondering why this wouldn’t work going forwards? Any ideas?

https://www.portfoliovisualizer.com/test-market-timing-model?s=y&symbol=VWUSX&timingWeights%5B2%5D=0&outOfMarketAsset=VUSTX&symbol1=VTI&endYear=2015&volatilityPeriodWeight=0&symbol2=MSFT&movingAverageType=1&windowSize=12&timingUnits%5B2%5D=2&timingModel=3&volatilityWindowSize=0&startYear=1988&assetsToHold=1&benchmark=^SPXTR&multipleTimingPeriods=false&timingUnits[1]=2&allocation1_1=100&outOfMarketAssetType=2&timingPeriods[0]=5&timingWeights[0]=100&volatilityWindowSizeInDays=0&riskControl=false&riskWindowSizeInDays=0&timingUnits[0]=2&periodWeighting=1&timingWeights[1]=0&windowSizeInDays=105&volatilityPeriodUnit=1&riskWindowSize=10&rebalancePeriod=1

@Luc: This briefly sums up my thoughts on back-tested market timing strategies. I can’t prove this, but I suspect the number of investors who time the markets with discipline can be neatly rounded to zero:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2012/05/17/why-i-have-no-faith-in-market-timing/

@CCP, couldn’t the same “do you have the discipline?” argument be made against any investment strategy. Don’t they all take discipline? E.g. staying in the market, investing more money when the market looks bad, rebalancing, tax harvesting, etc. Studies have shown that few investors achieve the rates of returns they should because of their behaviour.

@Luc, things to watch out about timing models and that website:

1.) There are implementation details that matter! The data presented by the website is flawed because it assumes you can sell at the end of each month and buy on the first day of each month with precision and no costs. This just isn’t the case; you’ll have slippage due to ask-bid spreads and gap up/down from the close of the last day of the month to the next opening day. Then there are trading fees and tax (in taxable accounts.) Taxes will be a challenge because the high turn over means you’ll pay taxes early before the money can compound vs. later once it has compounded. Also, with monthly trading you’ll run into the superficial loss rule so it will be harder to do tax loss harvesting… not impossible, but lots of bookkeeping and swapping between similar but not the same assets.

2.) Timing models like the one you gave suffer from being optimistic and leave you with no defense. Show some humility and don’t be like Long-Term Capital Management (google it) and ask yourself, what if the trading model is wrong at some point? Actually, I should be more direct and say it WILL be wrong at some point. What are the risks? With your portfolio you are 100% in stocks or bonds at any given point. So what if it’s wrong and stocks tank or bonds tank while you are holding them? If that happens you are fully exposed. With a simple 50%/50% portfolio you will have less risk because your exposure in each is lower and they are likely to be somewhat uncorrelated. This in my opinion is often the fatal flaw of all timing models and I will try to explain why below…

Let’s compare a passive vs. timing model of investing. For simplicity, let’s assume there are only three asset classes; cash, stocks and bonds. Let’s also assume that you want to manage risk and therefore you limit yourself to not holding more than 50% of you portfolio in stocks or bonds at any given time.

For passive investing, you hold a simple portfolio of 50% stocks, 50% bonds and rebalance to maintain this level of risk. Simple.

For timing investing, at any time your portfolio is limited to these extremes:

50% stocks, 50% bonds

50% stocks, 50% cash

50% cash, 50% bonds

100% cash

So, over time, on average you’ll be holding a fair chunk of cash that is not invested!

And that, in summary is the problem… to manage risk to the same level as a passive portfolio, you end up holding a lot of cash but then that means to match a passive portfolio you need to significantly outperform with your remaining invested, non-cash, assets. But how likely is that when at any given time, your non-cash investments can at best be the same as what would have been held in a passive portfolio? So you cannot win on the upside! Your only hope of making this work is by winning big is if your timing model helps you avoiding downside losing while keeping you in the market enough that you’ll also catch the upside gains. This is a hard road to travel and few have done it in practice.

@CCP and BrianG,

Thanks for your insights. It’s interesting how such a huge part of investing comes down to psychology and philosophy in practice, but in back-testing, only raw data is used – something us emotional, thinking human creatures will most likely have difficulty implementing in practice.

I’d be interested to hear if anyone has actually implemented a portfolio like this with robotic precision, (as unlikely as that may be for us humans), in a tax sheltered account. I know there will be drag through spreads, commissions etc, but that shouldn’t be too huge considering a 10 – 12 month SMA. I notice one commenter, Phil Kanter, on the link CCP provided above, said this type of strategy did help him miss 2008.

I’ve since learned that the strategy is basically the same as Meb Fabers (I didn’t know who he was till a few days ago), and more than likely, he got the idea from someone who got it from someone etc etc.

On the Couch Potato front, personally, I find just sticking to a buy and hold strategy also requires a type of robotic commitment to a plan of some sort, but my hunch is that having a plan that you truly believe in, through thick and thin, is one of the biggest investment hurdles to overcome. After all, isn’t that what this site and many others out there are all about? The execution is easy, making a plan that you’re 100% committed to is the hard part.

Yep, trying to just hold onto your hard earned cash can be, well, trying at times, but I’m willing to continue diving into empirical evidence until I have an investment philosophy in mind that I’m truly comfortable with.

I have been a follower of Ray Dalio and his all weather strategy, and incorporated it into my personal investing strategy. First, I believe Dalio’s asset allocations are not static, but rather are calculated and adjusted regularly to maintain “risk parity” (so that each asset class represented in the portfolio has an equal amount of risk). When an asset class, such as gold or long-term US treasury bonds, becomes more volatile and becomes an under-performer, the asset allocation for that position is often reduced. So there are times when the percentage of treasury bonds in the portfolio can be less than 50% or greater than 60%, and an under-performing asset like gold may only by 4-5%. This reduces the volatility of the all season portfolio even more than that of a static all weather portfolio allocation (my personal experience is annualized volatility runs in the neighborhood of 6.5%) , and that is why Dalio and others often use leverage with this strategy.

I think the primary concern for the all weather strategy right now is that, because it is heavily-weighted in US treasury bonds, and central bank intervention has kept long term interest rates artificially low for many years into this economic cycle, there is a risk that the eventual increase in interest rates will have a severe impact on bond portion of the portfolio. The market has been paranoid about this, and trying to anticipate the move, but of course, it is hard to predict the timing. The artificially low interest rates have also made it easier for hedge funds to increase margin buying and leverage, and an increase in interest rates may force them to liquidate some equities. Therefore, the concern is that the typical negative correlation between stocks and treasury bonds will be reduced, a detriment to all weather investing.

The bond vigilantes tried to force a premature move in interest rates back in 2013, which is why the all weather strategy performed so poorly that year. About that time, Ray Dalio went public and acknowledged there was a “weakness” discovered in the all weather strategy. A rise in interest rates doesn’t necessarily equate with a rise in inflation or equities, so that inflation protecting components of gold and TIPS doesn’t cushion the blow. Dalio reported to his investors that some “tweaks” were made to the all seasons strategy, but he has refused to say what they are publicly. But it is likely it some sort of interest rate swap/option vehicle that us small retailer investors may not have at our disposal. I am a believer in the strategy. However, I have temporarily reduced my treasury bond holdings by about 50% as well as my leverage (keeping about 12% in cash) until a more “normal” interest rate environment is established.

Finally, as evidenced by the 2008 crisis, there can be turbulent times when the correlations of all asset classes can increase dramatically towards 1 (and all fall in unison), and no asset allocation strategy, not even the all seasons portfolio, can protect you. Therefore, i believe it is important to deploy a “go to cash” stop loss strategy when the entire portfolio drops below a certain value threshold. But I have found that an all weather asset allocation strategy, combined with an overall portfolio stop loss strategy, can be successful and allow you to sleep at night.

Another great post Dan!

Taking a look at the hype from the hype master(s) that are out there, and logically incorporating the recorded facts from yesteryear and presenting them into a non hyped report is invaluable. To boot Dan you have a litany of readers that add very valuable insight when they post their concerns and observations as they have with this and many previous posts.

Cudos to CPP Dan and to the legion of loyal and intelligent readers!

I’m more confused than ever with Bond fund talk last little while. Experts say to go to short term bonds. Do long bonds pay less than short ones now days? For example does a 30 year bond pay less than a 5 year now days? I thought long bonds pay more and interest rate rise is good thing. I’m a common sense person, more interest is good and long bonds should pay more than short.

@Jake: The issue is not that short-term bonds pay higher yields than long-term bonds. It’s that if interest rates rise, long-term bonds will lose more value. In general, if you expect interest rates to rise you should keep your bonds short. Just remember that if you expect interest rates to rise you could be wrong.

This should help:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2015/05/18/how-changing-interest-rates-affect-fixed-income/

As far as I can see, the ASP differs from the CCPP (assuming the investor’s requirement for stability dictates 55% allocation to bonds) only in that:

1) The somewhat more than 3/4 of the bond allocation being in long term bonds compared to perhaps no more than 1/4, if any at all, being recommended in the CCPP

2) Of the remaining 45% available, only 30% are allocated to stocks in the PP, with 7.5% being allocated to Gold, and 7.5% being allocated to Commodities (versus all 45% being allocated to stocks in the CCPP).

3) The 30% stock sub-allocation is left unspecified in the brief outline of the ASP above (I could be wrong in that the essence of the ASP actually specifies the sub-allocation), whereas the standard CCPP sub-allocation is roughly 1/3 each Canadian, US and International.

Leaving aside #1) which has been already discussed above, and the fact that the ASP appears to be a prescription directed at US investors, while the CCPP is, well, Canadian, it seems that the essential difference is that the CCPP has kept the remainder of 45% all in stocks, while the ASP has taken 7.5% (of the total portfolio) out of this and spent it on Gold and another 7.5% to hold in Commodities. Dan has discussed the place (or not) of Gold and Commodities in a long term portfolio before. But I would be interested in his view on the effect of taking a well balanced 55%/45% CCPP and then carving off (squandering?) 15% out of the stock portion to buy Gold and Commodities.

The All Seasons portfolio was based on two basic principles that average investors don’t consider.

1) Principal of compounding returns

2) Principal of asset allocation being 95% of your investing gains over time – David Swensen (Yale)

The portfolio was designed with one specific question in mind for Ray Dalio which is: “If he couldn’t give any of his money to his children (roughly 20 billion dollars) and all you could do is give them an investment strategy, what would it be?”

The answer was the all seasons portfolio where all of his wealth is placed.

It was not marketed as the greatest portfolio of all time with market beating returns, but rather a safe place that anyone can put their money and watch it grow over time with minimal correction years enabling the investor to actually stay in the game long term. In Canada there is a record 1 trillion dollars in cash not being invested because they don’t believe in the stock market.

We all know “balanced portfolios” didn’t do well in 2008 or 2000 and the average person lost 30-50% of their portfolio and sold the majority of their stocks, bonds mutual funds, leaving them on the sidelines for 2 of the greatest bull markets that followed the crash. Most people cannot stomach losing 20% in a year, therefore gains are limited but losses are limited. The most important thing is to keep your money in the game for 30 years. The average investor cannot do that with crashes coming every 7-10 years.

I have a question. Since interest rates seem to be the topic of interest, I have attached a chart of the portfolio returns through periods where interest rates were up to 14% annually.

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/40004235/All%20Weather.png

Whats wrong with the chart? I’m no expert but it looks good to me.

With all that being said, most investors on this blog are not “average”

Cheers,

Sam

As much as I appreciate the critique, 1) Tony is actually not a motivational speaker and 2) The all seasons portfolio was designed by some one who follows those same principles and has the $$$ to show the result of using them.

If it’s a dart board for you, then throw darts. If it’s a gift for you, use it.

I really like the way Tony took a complex strategy and made it user friendly for the average american. He does this with all his programs and they are highly effective if you use them.

If I want to hedge half of my foreign equities, is the following portfolio reasonable? I recognize that emerging markets won’t be hedged here.

VAB – 25%

VCN – 25%

VXC – 25%

VEF – 12.5%

VUS – 12.5%

Thank you.

@CS: Yes, that would do the trick.

I find some people are a bit harsh on the Cash component. You’ll be grateful to have a cash component when something like 2008 happens. Everything is upside down these days to ARTIFICIALLY low interest rates, stocks being propped up by QE, and gold price being suppressed by central banks. It IS going to end very badly, and it will make 2008 look like a pleasant day in the park.

Great article. As with any back testing, past performance doesn’t guarantee future performance. This is especially true with the fundamental change occurring in the modern global economy. The All Weather/All Seasons portfolio performed very well in terms of risk aversion over the past 30 years due in large part to a 30 year long bullish bond market. When you extend out towards 75 or 100 years, the reduction in risk doesn’t make up for diminished returns from that portfolio, which in my opinion, is too bond heavy.

Check out my sample portfolio at my blog Building the Bank: buildingthebank.com

-Brian

My portfolio looks like this for long term

VCN-20%

VXC-40%

VAB-20%

VRE-10%

CGL.C-10%

stocks,bonds,reits,gold

even the example comparing PP and others to ASP shows the point of it without it being stated

lowest volatility of the groups

best return of those groups

the standard deviation and volatility is most relevant during those bad periods since the 70s to 2014 when investors would sell and take large losses in even a balanced approach

this is where the ASP would be the most beneficial

and that is the point

I thought I should follow up now that 2018 has come and gone. TLT (20+ yr bond) was up 7.25% in 2018, a calendar year with multiple interest rate hikes. And the exact All Weather ETF portfolio you shared was up 5.79% in the same calendar.

Calendar year return for Couch Potato ETF model portfolios:

Conservative asset allocation: -0.76

Cautious asset allocation: -1.62%

I’ll listen to Dalio over a couch potato.