When I update the performance of my model portfolios, the returns I use are based on the annual change in each fund’s net asset value (NAV). That’s the most appropriate way to measure an ETF’s performance against its benchmark index, but it may not be the return investors actually obtain in their own accounts. If you calculate your portfolio performance using your brokerage statements, you’re more likely to get the fund’s market price return, which may be quite different.

Let’s back up and make sure the terminology is clear. An investment fund’s net asset value (NAV) is the total value of all its underlying holdings. To use a simple example, if an equity fund’s portfolio is valued at $1 billion and there are 50 million units outstanding, its NAV is $20 per unit. In North America, a fund’s NAV is calculated once per day at 4 pm EST, when the New York and Toronto exchanges cease trading.

A mutual fund always transacts at its NAV, because orders are filled only once per day after the markets close. In other words, its NAV is also its de facto market price. But that’s not true for ETFs: their net asset value is still calculated at 4 pm, but they trade throughout the day, so their market price can change from minute to minute—just like an individual stock.

Of course, an ETF’s market price reflects its net asset value (NAV), so in theory these should always be very close. The ETF’s market makers estimate the NAV throughout the trading day and post bid and ask prices accordingly: if the NAV is $20, you might expect a bid of $19.99 and an ask of $20.01. But in practice things are rarely that tidy, and sometimes an ETF’s market price can differ substantially from its net asset value—at least temporarily.

These discrepancies can cause differences in the way an ETF’s returns are reported, so most providers include both market price and NAV performance on their websites. Here, for example, are the numbers for the BMO Mid Corporate Bond (ZCM):

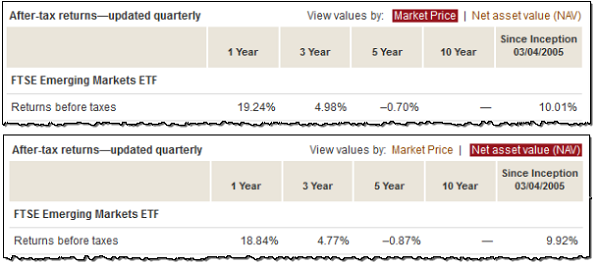

And here’s how Vanguard reports them on its US website, using the Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets (VWO) as an example:

As you can see, even over two or three years, the discrepancy can be 20 to 40 basis points. For index investors who often choose one fund over another because of small differences in fees, that’s a big deal. And in some cases the gap is much larger: in 2011, the iShares BRIC Index Fund (CBQ) lost 22.35% on a market price basis, but its NAV declined 23.51%, for a difference of 116 basis points. (Current market price returns are temporarily unavailable on the iShares website.)

Should I be worried?

This difference between market price and NAV returns no doubt raises a lot of questions. What causes the discrepancy? Which one is a more reliable measure of an ETF’s performance? And should I be worried about all of this?

To get some insight I spoke to Pat Chiefalo, director of ETF research and strategy for National Bank Financial. In general, the answer to the last question is no, you don’t need to be overly concerned, especially if you’re a long-term investor who holds your ETFs for many years. “Point-to-point is not a good indication of which ETF actually performed the best. Because nobody buys their ETF on December 31 and then sells it on December 31 following year.”

Chiefalo explained that large discrepancies occasionally indicate a genuine problem with the way the ETF is managed, but more often they reflect a pricing anomaly that is short-lived. “When you see a big difference it’s very important to know why,” he says. “We correct for a lot of the stuff in the performance numbers to make more apples-to-apples comparisons, and to see whether the problem was real.”

Unfortunately, retail investors simply don’t have the tools to investigate these discrepancies themselves. If they try, they’re likely to make bad decisions based on incomplete or misleading information. “I’m not going to say all ETFs are perfect, but there are a lot of reasons why someone could jump to conclusions when actually everything is fine,” Chiefalo says. So next week I’ll look more deeply into the reasons why market price and NAV can vary, with the help of Chiefalo and other specialists.

Since I’ve been doing a lot of ETF research lately I noticed that Vanguard shows the distribution of the price difference, typically on the Price and Peformance page. For VWO this shows that the ETF spends an approximately equal number of days trading above and below the NAV.

The internet stalking continues. :)

2 days ago I was browsing HXS’ documents page and found this gem of an ETF tracking error report. http://www.horizonsetfs.com/Pdf/Research/20130121_ETFPerformanceReview.pdf

Its author? Pat Chiefalo of course. Had never heard that name until 48 hours ago.

Your tracking error posts are some of my favorites to read. They expose issues that many of us might not otherwise discover on our own(or only realize after experiencing prolonged underperformance in our investments). http://www.financialwebring.org/forum/viewtopic.php?f=29&t=468&start=175#p493295

Hope you’ll get into INAV and its availability(or lack threof) for Canadian listed ETFs. Looking forward to the post(s).

I can’t say I’ve studied the discrepancy between market price and NAV closely, but this gap seems to be smallest for the broadest ETFs like XIU and VTI. I’m not too worried about losing 20 bps once in 20 years of holding an ETF, but those who trade in and out much more frequently should pay attention to this gap. I tend to assume that every trade I make I’m being taken for a small percentage by someone who is a better trader. The less I trade the better.

Dan, this is yet another interesting wrinkle I was totally unaware of. I never had any idea how much I didn’t know about index investing until I started reading your blog!

@Michael: Yes, the gap is smallest with large, frequently traded ETFs that hold liquid domestic stocks. International equity ETFs are a different story, however, as VWO attests. That will be one of the factors I discuss next week.

Trading as little as possible is always good advice, although as Value Indexer alludes to, investors should understand that there is no consistent bias here: sometimes the market vales numbers are higher than NAV, sometimes lower. In some cases trading might work in your favour, although it would just be dumb luck.

OK, a similar question then: What is the difference between a fund’s ‘Total Assets” and “Net Asset Value”? For example, globefund lists PHN Bond-D (PHN 110) as having “Total Assets” of $796 million, yet PHN lists the “Net Asset Value” on its site as over $2 Billion.

@Steve: Those two figures should be the same. My guess is it’s just an error on Globefund. Note that what we’re really talking about in the post is “NAV per share,” not the fund’s total net asset value.

Yes total assets and nav are the same but big differences result when one source quotes assets only for the series/class of units/shares you’re looking up while others report aggregate assets for ALL series.

Can’t also forget with ETF’s it’s pretty much impossible to buy at the closing price (unless you time things perfectly at 3:59pm) and your results are going to differ anyhow since every ETF changes in price during the day. Maybe for the good, maybe for the worse, but a small impact if you have a long horizon

I guess there is also a difference between short term price changes driven by individual transactions and systemic reasons.

An order at market might go through multiple entries in the order book with a different price. This is bound to nudge the price temporarily. Actually, this could happen quite easily for infrequently traded ETFs.

Do I have to be worried about this? I guess not, except to remember to always place limit orders.

@Aethelstane: It’s definitely a good idea to use limit orders all the time. But if you do place a market order for a thinly traded ETF, it’s unlikely to be filled at different prices. Remember, unlike with a stock, trading volume does not have a large effect on ETF liquidity, so your order should have no effect on the price.

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2012/09/10/etf-liquidity-and-trading-volume/

I’ve always wondered about this. Inherently it makes sense that to be able to trade ETFs “like a stock” could lead to price fluctuations that have nothing to do with the Net Asset Value. I sent an email to Rob Carrick of the Globe about this issue, but never got a response. So thank you, Dan, once again, for speaking truth.

I bought Powershares QQC which is a Nasdaq etf, Canadian $ hedged.

It has low trading volumes and I could never co-relate daily ups and downs with the QQQ.

On September 13, I bought 10 out of the 80 shares which traded on the TSX that day and they lost 10 cents while the QQQ rose 1.35%.

Powershares sent me a long explanation which followed your NAV theory of tiny discrepancies:

As of June 30, 2012, there were 550,000 units of PowerShares QQQ (CAD Hedged) Index ETF outstanding and 98.25% of the total net assets of PowerShares QQQ (CAD Hedged) Index ETF was comprised of 188,468 units of PowerShares QQQ. Thus, as of June 30, 2012, for each unit of PowerShares QQQ (CAD Hedged) Index ETF, 98.25% of the unit’s net assets consisted of approximately 0.3427 units of PowerShares QQQ (188,468/550,000 = 0.3427). Given that 98.25% of the net assets of each unit of PowerShares QQQ (CAD Hedged) Index ETF consisted of only 0.3427 units of PowerShares QQQ, it can be expected that the NAV per unit of PowerShares QQQ (CAD Hedged) Index ETF will be significantly lower than the NAV per unit of PowerShares QQQ.

It did not satisfactorily explain a 1.5% total discrepancy.

@Paul: I’m not sure what that explanation from PowerShares means. But you say you bought 10 shares, which would only have been a couple of hundred dollars. Is it possible that the trading commission is what caused the “loss” in your holding? The currency hedging may also cause the performance of QQQ and QQC to vary: we know that the hedging is not precise.

@CCP

Correct me if I’m wrong but aren’t there some mutual funds out there that simply buy the indexed ETF’s? If so, I would imagine they would gobble up any discount that might briefly appear while leaving the premium moments for the rest of us (arbitrage).

Your thoughts please.

Today (Friday ) I placed a limit order for 125 shares of a thinly traded order at noon. It was trading at 9.09 which is what I placed the order for. It was not even filled! Haha 4 hours and it was not filled because the ask price was 9.12. That was a first for me. Irony being come Monday it may even open at 8.90 (one never knows!)

@Ryan: The important point here (which I will expand on in the next post) is that differences in the market price and NAV cannot be reliably arbitraged, because they are usually very short-lived. Even if they could be arbitraged, I don’t think mutual funds would be the ones to take advantage.

@Death and Taxes: My guess is that 9.09 was the “last” price, which is not meaningful when you’re looking at a thinly traded ETF. When you place a limit order to buy, your reference point should be the ask, not the last price. I discuss this point in detail here:

https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2012/09/13/an-etf-pricing-puzzle/

Dan thank you for the education, I love this site, you really get to the heart of the matter.

I will see what Monday brings!