Last October, Justin Bender wrote a blog post explaining why GICs are more tax-efficient than bonds. The blog caught the attention of John Heinzl of The Globe and Mail, who wrote his own article on the topic a month later. Many investors are still surprised and confused by this idea, however, so I thought it was time to take another look.

It’s true that bonds and GICs are taxed in the same way. If you buy a newly issued bond with a face value of $1,000 and a coupon of 4%, you’ll receive $40 in interest each year, and this amount is fully taxable at your marginal rate. If you buy a $1,000 GIC yielding 4%, the situation would be identical. Nothing complicated so far.

However, in practice, things aren’t that simple. Interest rates have been trending down for years, and bonds issued when rates were higher now trade at a premium. Let’s use an example to explain this concept. Twelve months ago you bought a five-year bond with a face value of $1,000 and a coupon of 4%. Since then interest rates have fallen one percentage point. That means your bond now has four years left to maturity and is still paying $40 in interest, while new four-year bonds are paying just 3%, or $30. If another investor was in the market for a four-year bond today, which one would he want?

The answer is obvious: he’d want the bond paying more interest. But we know there’s no free lunch. The bond with the 4% coupon will now sell for a premium: it would be valued at approximately $1,036. (I’m simplifying the math here, because the concept is what’s important.)

Now there’s a trade-off: the buyer of your old bond will receive more interest, but at maturity he’ll collect only the face value of $1,000 and suffer a capital loss of almost $36. If both bonds are held for the full four years, their total return will be the same: in other words, both now have a yield to maturity of 3%:

| Premium bond | Bond at par | |

|---|---|---|

| Term to maturity | 4 years | 4 years |

| Face value | $1,000 | $1,035.71 |

| Price (initial investment) | $1,035.71 | $1,035.71 |

| Coupon | 4% | 3% |

| Yield to maturity | 3% | 3% |

| Interest paid over four years | $160.00 | $124.29 |

| Capital loss at maturity | -$35.71 | $0.00 |

| Total return (interest – capital loss) | $124.29 | $124.29 |

The upshot is if you’re investing in your RRSP or TFSA, it doesn’t matter whether you buy bonds at a premium, at par, or at a discount. With no taxes to pay, it all comes out in the wash.

Taxes change everything

If you’re holding fixed income in a non-registered account, however, the situation is quite different. The reason is that interest and capital gains/losses receive different tax treatment. And when you buy a premium bond, a greater share of your total return comes from fully taxable interest. Here’s an example using the same two bonds as above, and assuming the investor’s marginal tax rate is 40%:

| Premium bond | Bond at par | |

|---|---|---|

| Term to maturity | 4 years | 4 years |

| Face value | $1,000 | $1,035.71 |

| Price (initial investment) | $1,035.71 | $1,035.71 |

| Coupon | 4% | 3% |

| Yield to maturity | 3% | 3% |

| Interest paid over four years | $160.00 | $124.29 |

| Net interest after tax (40%) | $96.00 | $74.57 |

| Capital loss at maturity | -$35.71 | $0.00 |

| Total return (interest – capital loss) | $60.29 | $74.57 |

If you could subtract the $35.71 loss from the premium bond’s $160 in interest payments, then both bonds would deliver the same after-tax return. But you can’t do that: a capital loss can only be used to offset a capital gain, not to reduce interest income. Capital gains are taxed at only half your marginal rate, so in the above example, the investor who used the loss to offset a gain would save only $7.14 in taxes ($35.71 x 20%). That would bring his total after-tax return to $67.43—still a lot less than the bond purchased at par.

Remember, too, that tax on the interest is payable every year, while the capital loss can only be claimed after it is realized when the bond matures four years down the road.

Par for the course

So what does all this have to do with GICs and bond ETFs? The key point is that GICs never trade at a premium or discount to their face value. Unlike bonds, GICs don’t trade on the secondary market—you can’t buy a five-year GIC today and sell it to someone else at a premium next year if interest rates fall. As with a bond purchased at par and held to maturity, a GIC’s total return is made up entirely of interest, with no capital gains or losses. Its coupon and its yield to maturity are always the same.

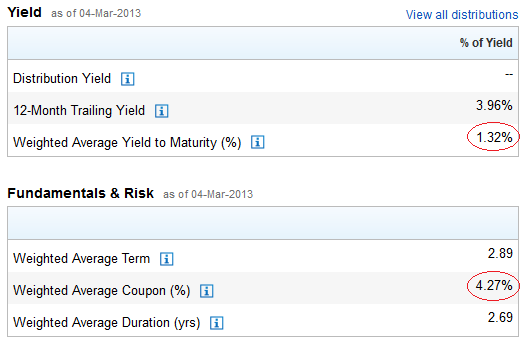

Compare that with bond ETFs today: virtually every one is filled with premium bonds. You can see this by visiting the fund’s web page, where you will notice that its coupon is higher than its yield to maturity. In some cases, the difference is dramatic, as with the iShares 1-5 Year Laddered Government Bond (CLF):

This ETF would be much less tax-efficient than a five-year GIC ladder, because that entire 4.27% coupon (minus fees) is fully taxable, even though the yield to maturity is just 1.32%. What’s more, GICs pay higher yields than government bonds: today you can build a five-year ladder with an average yield over 2%, with no credit risk and no chance of a capital loss.

ETFs do offer more liquidity than GICs, and there’s an opportunity for capital gains if rates fall and you sell the fund after its price has gone up. But if you’re a long-term investor who needs to hold fixed income in a taxable account, GICs are likely to be a better choice.

Thanks for another great post.

One thought/issue I have had with respect to this sort of “tax efficiency” discussion is the idea of theoretical efficiency versus actual, resulting from how and when the tax is actually applied to the income or account.

Let me give an example. In your case above, the premium bond pays $160 in interest, which would be deposited directly into your investment account. You would then suffer a capital loss of $36, bringing the dollar sum in your investment account to $124. The exact same as the face value bond. The difference here actually comes later – when at the beginning of the next year, you receive your T-slip with $160 of income that requires you to pay tax. You then have to pay the tax.

So I agree with your case 100%, that from a wholistic perspective, the Premium bond is less tax efficient (you do have to pay that tax at the end of the year). But from a practical perspective, I am not likely to have opened up my investment account, and withdrawn $64 to pay the income tax resulting from the T-slip I received. Actually, I probably just paid the tax and didn’t notice. So in that “pracitcal” regard, the value in my investment account is not different.

I hope this makes sense. Again, I agree totally from the theoretical perspective (and if we were talking about sums with 2-3 extra zeros, it would be very material). But for smaller investors, it seems likely that the “inefficiency” is just absorbed and unnoticed at tax time, and does not actually lower their “returns” (at least in the sense of account balance).

(Incidentally, I think the same can be true in reverse – say considering Foriegn Withholding tax in an unregistered account. It’s deducted immediately, and “in theory” you can get this back at tax time – but how many people do you know that actually file their taxes, then go back and deposit and reinvest $16.53 in foreign withholding tax that was deducted from their unregistered account? I’d say none. So in that sense, I consider that tax to be, for all practical intents and purposes, completely gone in an unregistered account, despite the fact that technically you can get it back.)

Thinking more clearly now, I suppose my thesis above is really that from a behavioral perspective, for small to medium-ish investors, and all things being equal, a “point of payment” tax (like a foreign withholding tax on an international equity, for example), is actually far worse than a “later on” tax (like income tax on a bond fund), since the former will be literally removed/deducted from your investment account (and therefore directly lower future returns), while the later is more likely to be “unnoticed” at tax time and unlikely to result in change to your investment account directly or to your investing habits. Hope that makes sense.

@Danno: Your description of how this would happen is not accurate. I simplified the math in the examples, but remember, the $160 in interest would actually be paid semiannually over four years (eight payments of $20 each). So you would get four T-slips during the life of the bond. Then when the bond matures, you would receive $1,000 in cash for a bond you bought for $1,037.50. Your description of this capital loss “bringing the dollar sum in your investment account to $124” is not correct.

And it makes no difference whether you pay the tax with cash from your investment account or from some other source. Same thing with foreign withholding taxes: whether or not you put the tax credit back in your investment account is irrelevant. Mental accounting aside, you’re either paying the tax or you’re not.

Doesn’t this debate only matter if you are maxing out your RRSP?

@MPAVictoria: Yes, perhaps I should have been more explicit. If you are able to hold all your investments in RRSPs and TFSAs, then the tax issue is irrelevant.

@CCP: I agree with you and understand completely. I think we are saying the same thing, and I just did a poor job of explaining my view. What I am trying to say is that I think there is a difference between what the calculation shows, and what the actual behavior of the individual will lead to.

So: “Your description of this capital loss “bringing the dollar sum in your investment account to $124″ is not correct.” Sure it is – IF you look at behavior. In Year 1, I will earn $40 in income in my investment account. So my account balance will now be $40. I will of course receive tax slips, for which I will owe $16 in taxes. This is the critical part……..I am very unlikely to open up my Questrade account, and withdraw $16 to pay those taxes in March. More likely, I just pay it out of my pocket. So my account still has $40 in it. Repeat four times, sell the bond for $1000, and at the end of it all, my investment account will most likely have the same balance. That’s my point.

Of course I have paid $64 in taxes out of my pocket over that 4yr period, so I am actually less well off (what your example is trying to illustrate). Agree 100%. All I have done is “duped” myself into thinking I have earned the same return, because I didn’t notice the four small tax payments of $16. But I would argue that is exactly, in fact, what most small investors will do – just not realize the $16 higher tax bill every year, and buy one less Latte.

The inverse is true with the foreign withholding tax. So I place EAFE Equity in my unregistered account, thinking I’m being tax-efficient because I can get that tax back. But that’s the calculation – not the behavior. Unless I am disciplined enough to actually look at my T-slips, figure out how much tax I got back, and REdeposit it back into my account, then I’ve really actually duped myself in the opposite manner. Again, you are 100% correct, I DID get the tax back. But if it’s a small amount, and I don’t redeposit that $16.53, and instead just buy a Latte, then my investment account balance really and truly is that much lower, as if I had paid the tax. Do that every year for 10yrs, and you’ve lowered your return by that amount, effectively. (although you got ten Grande Latte’s in exchange :-)

Hope that’s more clear. Again, I’m agreeing with you completely, just think that the way that most investors, real world, and especially smaller ones, are likely to handle that tax treatment, will lead to different outcomes.

Interesting analysis. I guess if interest rates rise in the future and bonds are selling at a discount, it may make sense to switch back to bonds in taxable accounts to get the favourable capital gains tax treatment (assuming that returns are otherwise similar).

Another thing to consider are the tax implications of holding income instruments that are tax advantaged, such as dividend payers, in registered accounts – the yield must be considered as well. With yields so low on GICs and bonds it may make sense to hold more dividend producing ETFs in registered accounts because of their higher yields. I still think stocks should mostly be held in unregistered accounts because of tax effects with rebalancing (favourable cap gains treatment and offsetting capital losses cannot be used in registered accounts). There was an article about this in the Globe yesterday:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-investor/investment-ideas/strategy-lab/dividend-investing/busting-a-myth-why-dividends-and-rrsps-belong-together/article9318411/

This is a bit of a side issue, but I am wondering why you have real return bonds (XRB) in The Complete Couch Potato model portfolio but not in the Über-Tuber?

@Noel: The Uber-Tuber was my attempt to mimic Dimensional Fund Advisors, and their fixed income strategy does not include real-return bonds.

@CCP: In case you were wondering if you were being overly redundant, or too elementary, you were not. I found this topic very challenging, and I totally appreciated your laborious step by step explanation, in words of one syllable, as it were.

I actually had read Justin Bender’s article before (you provided a link in a previous post). I must admit, I read it several times, and although he provided quite an explicit accounting, I just didn’t “see” how the tax got to be higher with Bonds vs GICs outside a tax sheltered account; I just accepted the raw conclusion and memorized the rule. With your explanation (perhaps my earlier familiarization experience helped a little, I don’t know) I finally understood “how” the tax treatment on Bonds and Bond Funds is more onerous than on GICs, and now I can explain it to someone else. Thanks!

Here’s something I’ve wondered about. Preferred shares generally trade at lower effective YTMs (or YTW where appropriate) than bonds of similar credit risk. The primary reason generally given is that they receive preferential tax treatment, so taxable investors are willing to pay a premium for them.

If that’s the case, why does this not happen with bonds? One would expect that premium bonds would trade at higher YTMs than par (or less-premium) bonds, for exactly the same reason, but this appears not to be the case.

Presumably the reason is arbitrage by tax-free investors, but if so, why does this not happen with preferred shares as well? ISTM the reason is that arbitrage between preferred shares and similar corporate bonds is not risk-free and is therefore limited, whereas arbitrage between government bonds with various coupons is completely risk-free, and therefore eliminates all but an infinitesimal difference.

So I guess I answered my own question. Preferred shares do generally have lower yields in part due to their taxation, but that difference is not (entirely) arbitraged away by tax-free investors due to the risks involved in doing so (risks which of course affect pricing in other ways as well).

I’m just working though how GIC’s could be used in my non registered account. Maybe this seems basic but can I purchase GIC’s through my discount brokerage? I use TD Waterhouse and currently use TDB8150 (1.25%) as well I have some VSB in the same account and would be interested in possibly switching to a GIC. Any suggestions? I just read about Maxa Financial which offers a 1 year GIC at just over 2% but is not CDIC insured. How secure is the Deposit Guarantee Corporation of Manitoba?

@CCP I know you we’re trying to keep this simple, but correct me if I’m wrong. All these blog post by the industry as well as your self fail to explain that the beauty of an RRSP is compounding tax free growth?

Example, in a non tax sheltered account every year I lose a portion of my principle to tax. This is a fee on my investment. And acts just like inflation or a MER.

But in an RRSP or TFSA, 100% of my principle grows the next year and years after. And they get taxed in the end?

All things being equal I should have faster growth in my tax sheltered accounts then non sheltered, Or is my math wrong?

@Phil: Yes, you can purchase GICs via TDW or TD “Direct Investing” as they are now rebranding themselves. On the column on the left side of “Webbroker” click on “Fixed Income.” On the top of the page you’ll see a link to “GIC Rates.” You’ll find a listing of issuers and rates separated out by term length. In the upper right hand corner is a telephone number for fixed income specialists. You need to call in your order. It cannot be done online.

@Phil and Russ: Thanks for raising an important point. You can buy GICs through most discount brokerages, though the details differ. At RBC and BMO you can see the whole inventory of choices and you can select whichever ones you want. At Scotia iTrade you have to call and do it by phone: sounds like TD is similar.

@Ecoheliguy: You raise a lot of points, but in general, yes, an investment will always compound more quickly in a tax-deferred account. Clearly a TFSA is preferable to a non-registered account in just about every way. With an RRSP it’s not so simple, because it’s tax-deferred, not tax-free. If you remain in the same tax bracket for your whole life, the amount of tax you ultimately pay may be the same whether you use an RRSP or a nonregistered account.

Dan, I have two questions:

1. What does this mean for RESP accounts, as I’m not certain how they are taxed; and

2. Can you contrast GICs and “vanilla” bond ETFs with a tax-advantaged ETF like iShares’ CAB? (Background: https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2011/06/20/understanding-claymores-advantaged-etfs/)?

Thanks.

Just a minor correction to CPP’s answer to Ecoheliguy: in the unlikely event that you stay in the same tax bracket your whole life, it’s the amount you make that stay’s the same between investing in an RRSP or in a taxable account (not the amount of tax paid). In the RRSP, your growth with have compounded more so the account will be worth more, but you will also have to pay more tax in the end. It turns out to be a wash. Simple 1 year example:

(1 + rate_of_return) * [(1 – marginal_tax_rate) * initial_money] = (1 – marginal_tax_rate) * [(1 + rate_of_return) * initial_money]

Where the left-hand-side is the non-registered case and the RHS is the registered case.

In this constant tax bracket senerio, you’re actually much worse off in the registered account if you hold equities, since you convert the capital gains from 50% taxable to 100% taxable.

@Michael: All growth in a RESP is tax-sheltered, so there is no tax advantage to GICs in these accounts.

Comparing traditional bond ETFs and GICs with CAB would be extremely difficult, in part because CAB’s distributions seem to vary unpredictably (sometimes return of capital, sometimes capital gains). I’m not even sure where to begin.

@Kiyo: I hesitate to get into a math argument with you (because I will lose!), but I think you’ve touched on a common misunderstanding. Remember that to make a valid comparison you cannot assume, say, $1,000 contributed to a nonregistered account to $1,000 contributed to an RRSP, because the former is made with after-tax dollars. John Heinzl recently did a good piece about this. See Myth #2:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/globe-investor/investment-ideas/beware-of-these-three-rrsp-myths/article9235153/

@Kiyo: “In this constant tax bracket senerio, you’re actually much worse off in the registered account if you hold equities, since you convert the capital gains from 50% taxable to 100% taxable.”

Actually I believe this is incorrect. The problem is that you have ignored the value of the immediate tax rebate resulting from the RRSP contribution.

Consider an investor with $1000 to invest. For ease of math, we’ll pretend he’s in a 50% tax bracket today (so 25% capital gains tax) and will be later too.

If he puts his $1000 in an unregistered account, and earns 5% per year for 10 years, he will have $1628. He will then have to pay capital gains tax of $157 (628×0.25) and will be left with $1471.

Now, if he has that same $1000 after-tax amount to invest, he can actually put $2000 into an RRSP (borrow $2k today, deposit it, and in the spring you’ll get $1000 back, leaving your net at the same $1000). In the RRSP, if his $2000 grows at the same 5% for 10yrs, he will have $3257. When he withdraws it, it will be subject to 50% tax now, leaving him with $1628 – MORE than he had in the unregistered case.

The reality is actually probably even more favorable towards RRSP, since it is unlikely that the asset’s entire 5% return came entirely from capital gains – more than likely some came from a yearly dividend, which would have been taxed/eaten away at every year in the unregistered account, making the number even lower.

So IF you will be in the same or lower tax bracket later, and IF you compare apples to apples in terms of the initial investment (said another way, you are a disciplined investor and don’t spend the income tax refund on a vacation), RRSP will be a better bet. If you are in a HIGHER tax bracket later, it’s probably no good.

@ Russ, Thanks.

CCP, great post. I had read Justin’s post a few months back and I am left with the same question now as I had then. As Michael James highlighted above, doesn’t this math only hold in an environment where current interest rates are lower than historical rates? If the example was a 2% coupon bond with a 3% YTM and 4 years to maturity, the bond would have a discounted trading value of ~$963 . In this example the tax treatment of capital gains would work in your favour. If my math is correct, the after tax return for this example would be ~$78 which is greater than the $74.57 for a par bond. Could a long term investor, who expects interest rates to fluctuate, take the approach that some periods this phenomenon will be a drag on your portfolio and other periods it will bolster it? If so then the decision between GICs and bonds could be limited to the assessment of relative returns and credit risk (or incur the fees and taxes associated with adjusting your strategy to the interest rate environment).

@Adam: If and when we are in an environment where ETFs are full of bonds purchased at par or at a discount, then yes, the tax situation will change. But we will have to see several years of steadily rising rates before that happens. You’ll know we’re there when ETF coupons are lower than their yield to maturity, and I’m unaware of any fund where that is case.

There is no reason why you can’t choose GICs over bond ETFs now and then make a change if and when conditions warrant. Remember, we’re talking about short time horizons here, so these are not irreversible long-term decisions. One-fifth of the GIC ladder comes due every year, so you can always reconsider the current climate before reinvesting that money.

I think I will look into cashing out XBB in my taxable account and moving it to my TFSA. Thanks!

@CCP I didn’t mean to indicate that any bond ETFs had a coupon less than their YTM. I was simply trying to highlight that this strategy has benefits during some periods (now) and detriments during others. An interesting, and more complex analysis, would be to see whether over perhaps a 30 year period if an investor would be ahead after fees and taxes by switching between bonds and GICs versus using one for the entire period. My perhaps unwarranted concern is that when you account for taxes and fees associated with switching you erode the benefit you highlighted. Also, assuming you construct a 5 year laddered GIC, it will take 4 years to fully transition from GICs to bonds once the market indications become apparent. As always, I appreciate your insights.

@Adam: I understood your point, and you are correct in theory. But this is one of those situations where I worry investors will make simple decisions complicated. Today, bond ETFs are filled with premium bonds and are therefore tax-inefficient. That we know for sure, so that should be the basis for the decision. Modelling scenarios over 30 years and making assumptions about taxes and fees would involve so much guesswork that the analysis would be useless.

@Danno and CPP: Subtle and beautiful! In an unregistered account you are taxed twice, on the initial income and on the investment income. In the registered account you are only taxed once. I can’t believe I missed this.

Thanks for the examples!

@Kiyo: Almost everyone misses this—and even after it’s pointed out to them, some people still don’t buy it. :)

Looks like this may have been hashed out above, but I believe this statement is incorrect: “If you remain in the same tax bracket for your whole life, the amount of tax you ultimately pay may be the same whether you use an RRSP or a nonregistered account.”

If you remain in the same tax bracket your whole life, an RRSP and a TFSA should be the same, and both should be far better than a nonregistered account. The only exception would be if you purchased a non-dividend paying security and held it for a very long term capital gain.

The main advantage of both TFSA and RRSP is that incremental income from your investments is tax free. Take a simple example where you buy a bond with a 5% coupon and hold for 10 years. Say you start with $1000, before tax. In an RRSP, you will get to invest the entire $1000. 10 years’ growth at 5% per year leaves you with $1628. You then withdraw from the RRSP and pay tax. Let’s simplify and say you pay a flat tax rate of 30%. So you’re left with $1140 after tax.

Now let’s say you used a TFSA instead. So you get taxed at the beginning and have only $700 to invest. $700 with compound annual growth of 5% over 10 years becomes $1140, which can be withdrawn tax-free.

Finally, say you invest in a nonregistered account. Again you get taxed at the beginning, so you start with $700. Each year you earn 5%, but you get taxed on those earnings (unlike above), so your investment actually only grows by 5% * (100%-30%), or 3.5%. That leaves you with $987 after 10 years.

If you expect to be in a lower tax bracket at retirement, all else being equal, an RRSP may be better than a TFSA. If you expect to retire rich, a TFSA may be better than an RRSP. But either one is almost certain to be better than a non-registered account.

Great post. @CCP – does the opposite hold true? If I purchased a strip bond, or zero coupon bond in a taxable account, could I hold to maturity and make minimal bond interest with a capital gain? Or would arbitrage eliminate any value in doing this?

Thanks.

Also I assume this would only apply to the retired investor who would have decreasing registered account space, and high need for fixed income. Any thoughts?

Thank you and Justin Bender who seems to have first publicly pointed this math out.

1) I’m still guessing that most people fortunate enough to have to hold fixed income outside of a registered account would have looked at the tax-advantaged product Michael Davie brought up: CAB – where you are promised the return of the index (minus fees) as capital gains/ROC rather than interest income. I must admit that I’m not smart enough to do the math, and maybe I’m not clear on exactly what CAB promises as the return in relation to the bond index, but I intuitively feel that if you can get past the risk behind the forward agreement, the savings in converting returns from interest to capital gains would far outweigh trading of bonds at a premium – even at the high MER of CAB.

2) Every time I read that one will suffer a capital loss by holding these bond ETFs I wonder if it is a loss that can be “harvested” towards capital gains elsewhere in the portfolio – in that case, does it really matter?

3) I might be confused about the terminology, or the difference in holding a bond vs a basket of them in an ETF, but if a long term investor is holding the bond for longer than the average duration, are the bonds still considered at a “premium”? ie: as long as you hold the 10 year bond for 10 years, don’t you get all the capital back no matter what happens to interest rates?

Hi Dan,

Thanks for covering this topic again. I followed your and Justin Bender’s earlier advice and moved my fixed income investments from a taxable account into a high interest savings account (HISA).

At some point in the future, interest rates are going to increase, and bond ETFs will eventually be holding par or discount bonds. In the interests of true DIY investing, I wanted to be able calculate when to make the move from GICs/HISAs back to bond ETFs.

I used Excel to set up a table like yours in the post, and used the present value (PV) function to calculate the exact “Price (initial investment)” needed.

I haven’t done a present value calculation since high school, in the 1970’s, so while I think I got it right, I’d appreciate anyone’s feedback who wants to double check my reasoning. Using Excel’s terminology:

Price (initial investment) = PV(rate,nper,pmt,fv,type)

PV = present value, the cost of a premium bond ($)

rate = yield to maturity (%)

nper = term to maturity (years)

pmt = coupon (%) * face value ($)

fv (future value in the PV calculation) = face value ($)

type = 0 (interest paid at the end of the period)

Using this formula gives essentially the same results as your tables in the post (PV = $1037.17).

Once the spreadsheet is set up, it’s easy to calculate expected returns on real bond ETFs by plugging in their current numbers. Using your example bond ETF (CLF) investing $1000 for 2.89 years in an account taxed at 40% will give a total return, after taxes, of -$9.07. I think that really drives home the attraction of GICs in a taxable account.

edit: the link I reference for my point/question #3 above is: https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2011/07/07/holding-your-bond-fund-for-the-duration/

When “attempting” to keep my portfolio balanced how do I treat FIE.TO when it comes to classification as to whether it is a “equity etf” or a “bond etf”. I have it in my tfsa so am not concerned that part of the distribution is a return of capital as far as tax implications. Currently I own in my wee portfolio

ZRE.TO 9.46%

ZXC.TO 6.14%

ZEF.TO 19.55%

ZLB.TO 7.96%

HNY.TO 3.36%(I will probably pick up more of this one)

HXT.TO 34.39%

FIE.TO 9.63%

SPLV:US 9.40%

In the next 8 months I am going to be applying my max allowable in order to fill up my tfsa. I only have about 20k of room left to contribute to my RRSP as my pension contributions usually exceed my RRSP allowed. So within the next year or two I will begin to build a non registered account( so yes will have to pay close attention to tax liability of certain investments at that time but will worry about that at a later date.)

@SleepyDoc: A premium bond is a bond that was issued at some point in the past, and is now trading above its par value. If you hold it to maturity, you will get back the par value, thus taking a capital loss (the amount you paid for it, minus the par value that you receive for it at maturity). Yes, this capital loss can be used to offset capital gains. However, it is still a problem, because only 50% of capital gains are taxable. So you receive extra interest (100% taxable) in exchange for reducing capital gains (50% taxable). Not only that, you have to pay the taxes on the interest up front, and only receive the savings from the capital loss when you sell the bond or it matures. (And only if you have capital gains to offset.)

As for CAB, not only is the MER somewhat high, there is also a large cost to the forward agreement (an additional 0.55 to 0.75%, paid by the fund), and the duration is fairly high. You’re right that converting income to capital gains largely solves the problem of premium bonds. However, after fees, the yield to maturity is only around 1%. You can easily get twice that with a 5-year GIC ladder (even a bit more if you shop around), and with far lower duration (lower interest rate risk). So regardless of tax bracket, you will end up with significantly more, even after taxes, and at lower risk. The only downside is illiquidity. (Although you could probably go to cashable GICs and still come out ahead if you really needed liquid funds.)

@D&T: Looking at the holdings of that fund, it’s about 15% bonds, 15% preferreds, 65% equities (mostly big banks), and 5% REITs:

http://ca.ishares.com/product_info/fund/holdings/FIE.htm

So that’s how you’d consider it in your portfolio. (To simplify further, you can think of preferred shares as 2/3 bond, 1/3 equity, and consider the REITs part of your equity allocation.)

That said, why pay 1% MER for a fund that essentially holds CPD, CBO, and a few bank stocks? There’s really no reason to hold preferred shares in a TFSA, so you could get the same thing at a fraction of the price with 1 part CBO to 3 parts XDV. (Although personally I’d remove the income focus entirely and just add to your HXT, or switch to ZCN for a bit more diversification.)

In case you were wondering ;), FWIW personally I’d also drop the gas futures and foreign bonds, seeing them as speculative, and instead look to add international equity diversification with something like VXUS. (As well as probably increasing your domestic bond allocation to keep the ratio the same.)

The low volatility focus is interesting and may well pay off. I’m not sold on it myself, but it certainly looks potentially promising.

@CCP: Any chance of adding the ability to edit one’s comments at some point? (Maybe just for a few days or something, to prevent the possibility of old comments being gutted?) Don’t know how challenging that would be with your setup, but it sure would be nice to be able to quickly fix it when I inevitably write “ad” instead of “at”, etc.

Thank you Nathan!

Dang I knew people would think I was nuts for grabbing a small part of HNY ( it is paying 14-16% distribution which is why I grabbed it when it was 8.59/unit but if things go south on it or the distribution drops I will dump it for sure!). I can definitely see the value in picking up VXUS! That is a lot of inflow of capital recently.

Thank you for your help as I am pretty new at this, but loving every minute of it!

@Nathan: The WordPress theme I use does not allow readers to edit their own comments. I’m not sure whether other themes offer that capability. I often correct obvious typos in comments when I notice them.

CCP, thank you for another informative post. The point is well made regarding long-term fixed income investment. In my opinion, there is still a place for premium bond ETFs like CLF or CBO, though: Capital preservation for short term holdings.

Imagine that you have a couple of $100k you may need at some point in the next 1-3 years. Redeemable GICs pay less than premium bond ETFs. Also, the risk of loss of capital is tied to the duration, hence the ETFs protect you better against a potential rate increase.

If there is another vehicle beating CLF and the like in this scenario, I’d love to hear about it.

@Aethelstane: Thanks for the comment. I think you’ve misunderstood a few important points about how bonds work. Bond ETFs are generally a poor choice for those who want to preserve capital over short periods. Both CBO and CLF have a duration of approximately 2.7 years, which means an increase in interest rates could lead to a negative total return over any period less than that.

If you want to preserve capital for less than three years and also enjoy liquidity, there really is only one option: a savings account.

@Aethelstane,

In addition to the concern about loss of capital for terms less than 3 years, CLF does not appear to be the best choice even assuming it’s held for 3 years. The expected returns for $100k invested for 2.89 years (the average term for CLF) are shown below for taxable and non-taxable accounts:

Taxable account (40%)

bond ETF (CLF) -907

GIC (2%) 3756

savings account (1.35%) 2584

Non-taxable account

bond ETF (CLF) 4029

GIC (2%) 6260

savings account (1.35%) 4307

There are some good answers to lessen the tax burden of interest bearing securities here.

http://m.theglobeandmail.com/globe-investor/personal-finance/bulls-bears-and-baseball-tax-strategies-for-investors/article4192320/?service=mobile

I realize the thrust of the discussion was GICs vs Bonds in a Taxable account. However, for those actually contemplating the next step, that is putting money into Savings or GICs, the interest rates quoted above may be in line with what you would be offered at your local branch of Your Big Bank, but are totally outperformed by the rates offered by smaller institutions, for instance Implicity Financial of Manitoba, which offers 2% on savings accounts, 2.05% on a 1 year GIC, and more for longer terms, e.g. 2.85% on a 5 year GIC. The capital is backed by the Deposit Guarantee Corporation of Manitoba, which I understand is solid.

@Nathan: Thanks for clearing up my capital loss and holding to maturity questions (re-reading the original article 5 times also helped, as CCP discussed the capital loss math but I didn’t get it the first time around!). I’m a little surprised that you feel the yield would be so low after fees and taxes. The ishares website is down right now, but CCP’s article last year indicated returns should be higher: https://canadiancouchpotato.com/2011/06/22/claymore-advantaged-etfs-costs-and-risks/

@CCP: Another thing that I was wondering is wether a 5 year GIC ladder is truly comparable to holding a broad basket of short and long government and corporate bonds like in XBB or CAB. I realize that everyone is on a short term bond bandwagon right now, but isn’t the point for the long term investor holding as diverse a portfolio as possible – despite all predictions the long term bonds had excellent returns over the last few years. As the saying goes…. the tax tail shouldn’t wag the investment dog …

@sleepydoc: According to the iShares site, CAB’s holdings have a weighted average yield to maturity (YTM) of 2.08%. Once you subtract the approximately 1% in fees, you’re left with about 1%. Interest rates have fallen since a year ago, so it was likely somewhat better last year.

As for the other, I’m not CCP but I’ll throw in my 2 cents since I’m commenting anyway! :) Keep in mind that the point of diversification is to reduce risk. With CDIC-backed GICs and government bonds, that’s not an issue, because there effectively is no credit risk. The only risk with these types of instruments is term risk. ie: sensitivity to interest rates. So a diversified portfolio of long and short term bonds is in fact more, not less, risky than a more concentrated portfolio of short term government bonds or CDIC-backed GICs. If you’re being compensated for taking on that additional risk it may make sense, but in the current situation, the opposite is in fact the case. So yes, it’s possible that, like any volatile asset, you’ll get lucky with long term bonds and have them go up. But in order to add volatility to our portfolio, we want to have an *expectation*, not just a chance, of being fairly compensated. (As is the case with equities compared to bonds.) When we compare long term bonds with GICs at current rates, that expectation isn’t there.

“If you want to preserve capital for less than three years and also enjoy liquidity, there really is only one option: a savings account.”

Yep! And fortunately, you can easily get a savings account today that pays more than CBO or CLF, without any of the associated risk. People’s Trust’s e-savings account for example is paying 1.9% at the moment I believe, compared to CBO’s YTM of 1.59% after fees. (1.18% for CLF.) And that’s not even taking into account the risks of the bond funds.

Heck, even if you don’t want to move the money out of a discount brokerage account, the various banks’ HISAs pay around 1.25%, again, completely risk free. TDB8150 at TD Waterhouse for example. So even if taxes aren’t an issue, why earn less with CLF and take on interest rate risk for no reason?

@Nathan: “So a diversified portfolio of long and short term bonds is in fact more, not less, risky than a more concentrated portfolio of short term government bonds or CDIC-backed GICs. If you’re being compensated for taking on that additional risk it may make sense, but in the current situation, the opposite is in fact the case.”

I’m confused. I’ve always held XBB as the bond component of my portfolio. Are you suggesting that I should shorten the duration of my bond component by switching to CBO or CLF due to an expectation that interest rates will increase? I don’t doubt that XBB is more risky than CBO or CLF due to the longer duration, but why am I not being compensated for the risk? Doesn’t the efficient market hypothesis hold for bonds? Don’t get me wrong – I do expect interest rates to increase, but as a long-term investor, I’m prepared to ride it out. I’d think that changing bond strategies to suit interest rate expectations is a form of market timing.

Well one could wait for interest rates to climb, there would ensue a huge sell off of bonds currently trading for a premium, with proper timing buy them at a discount and wait till they mature.

@Smithson: “Are you suggesting that I should shorten the duration of my bond component by switching to CBO or CLF due to an expectation that interest rates will increase?”

No, not at all. I have no idea what interest rates will do tomorrow, and you’re right that XBB does have a higher YTM than CBO, which has a higher YTM than CLF, as you would expect due to increasing risk.

What I’m saying is that a 1-5 year GIC ladder has exactly the same risk as CLF, but pays more than ANY of those options. So why take on more risk to earn less? The only way you win with XBB over a GIC ladder is if interest rates drop, and only if you sell to capture your capital gain. If they stay the same or rise, or even if they drop and rise again and you don’t sell (which is the plan if you’re holding long term), you’re better off with the GICs, since they pay higher interest. Again, this is even in a tax-free account, although in a taxable account the case is even stronger.

So to summarize, I’m not making any predictions of future interest rates; I’m saying that it makes sense to choose the best option for a given level of risk right now. Here’s an analogy. Say a competitor comes out for XBB that holds exactly the same index, but has a lower MER. It would be a better choice, right? Well, a 1-5 year GIC ladder is like another CLF with a 1% lower MER.

Oh, and what if interest rates do increase to more historically ‘normal’ levels? That would cause both XBB and your 5 year GIC ladder to drop in value, but XBB by 3 or 4 times as much. Once rates get to the point where XBB is once again paying a reasonable premium to compensate for its additional risk, you can start moving money from the GICs back into XBB as they come due. Not only will you have collected higher interest all along the way, you’ll get to buy XBB at a cheaper price. (But again, even if rates stay the same indefinitely, you’re still better off.)